For the first time in its history, the 73rd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) – the world’s premier neurology meeting – was held in a fully virtual format from April 17th to 22nd 2021

Welcome to AAN 2021

James Stevens, AAN President

The 2021 virtual AAN annual meeting was centred around a rich educational and scientific programme including over 90 expert-led educational courses, more than 2000 scientific abstracts and seven key plenary sessions featuring leaders in neurology.

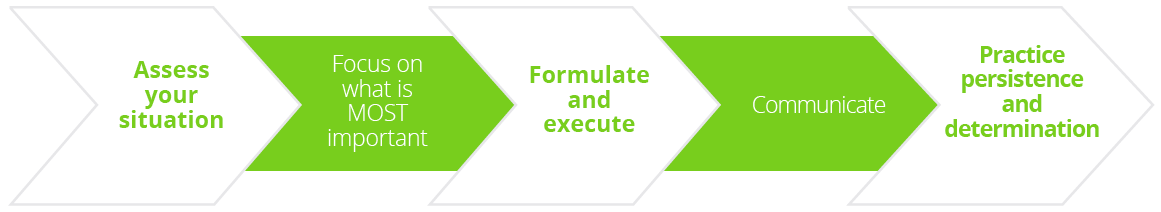

AAN President James Stevens, Fort Wayne, USA, began this key plenary session with presentation of the President’s Award followed by the Presidential Lecture entitled: ‘Disruption: How to Pivot from Uncertainty to Success - the AAN Story.’ Dr Stevens proposed a focused five-pronged approach to navigating crises such as COVID-19.

Five-pronged approach to navigating crises such as COVID-19.

“What a year it has been - unprecedented does not even begin to describe what we have all been through. We’ve faced uncertainty, exhaustion and challenge but we are emerging stronger, resilient and prepared to face our new future. ”

President James Stevens, Fort Wayne, USA

Orly Avitzur, AAN President-Elect

The 2021 virtual AAN annual meeting was centred around a rich educational and scientific programme including over 90 expert-led educational courses, more than 2000 scientific abstracts and seven key plenary sessions featuring leaders in neurology.

There then followed a brief welcome address by AAN President-Elect Orly Avitzur, Tarrytown, USA, who will be charged with leading the academy over the next two years. As we enter the recovery phase of the pandemic, Dr Avitzur outlined some exciting AAN programmes for the future including an increasing focus on hybrid educational and scientific meetings, studies to support telemedicine and an expanded emphasis on well-being.

DEMENTIA

Assessment of Rapidly Progressive Dementias

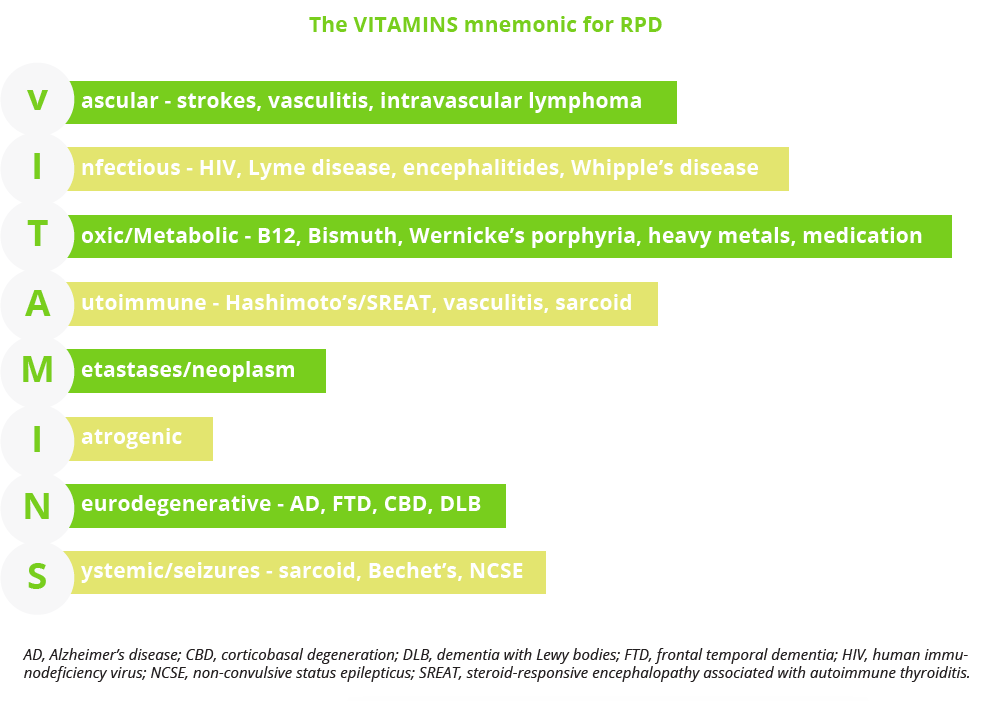

Rapidly progressive dementias (RPDs) can be challenging to identify as the differential diagnosis is broad and includes many potentially reversible conditions. Michael Geschwind, San Francisco, USA, reviewed the optimal diagnostic approach to prion diseases and other non-autoimmune RPDs. Describing Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) as the ‘great mimicker’, he stressed the importance of verifying the disease time course, being thorough in the clinical evaluation of patients with RPD - using the VITAMINS mnemonic as an aid - and carrying out brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Autoimmune aetiologies should always be considered and it is vital to diagnose infections and tumours early for potential treatment. When in doubt, Prof Geschwind advised that patients should be admitted for a quicker and more thorough work-up.

The VITAMINS mnemonic for verifying RPD disease course

Jeffrey Gelfland, San Francisco, USA, examined antibody-associated and other neuroinflammatory RPDs which represent an important and common disease subset. Dr Gelfland noted that the incidence of autoimmune encephalitis has increased 3-fold in the last decade, driven by the detection of new central nervous system (CNS) autoantibodies, and now rivals that of infectious encephalitis. Empiric immunosuppression for autoimmune encephalitis can involve acute, induction or maintenance strategies dependent on disease severity and treatment goals. Other potential autoimmune/neuroinflammatory causes of RPD include CNS vasculitis, cerebral amyloid angiography-related inflammation, demyelinating disease, neurosarcoidosis and neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus.

Diagnosis and Management of Frontotemporal Dementias

How many dementia cases are estimated to be FTD

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is an umbrella term for a group of disorders characterised by progressive decline in behaviour or language, which is accompanied by neurodegeneration of the frontal or temporal lobes. Elizabeth Finger, London, Canada, gave an overarching review of FTD, focusing on the behavioural variant (bvFTD). Consensus criteria for possible bvFTD require three or more behavioural/cognitive symptoms to be present while, for definitive diagnosis, histopathology evidence of FTLD or a known pathogenic mutation are additionally required. Work-up for suspected FTD includes functional, social/cognitive and neuropsychological assessments, neurological and clinical examination, and structural and functional neuroimaging. Fluid biomarkers such as CSF and serum testing of phosphorylated tau isoforms can also be useful to rule-out AD.

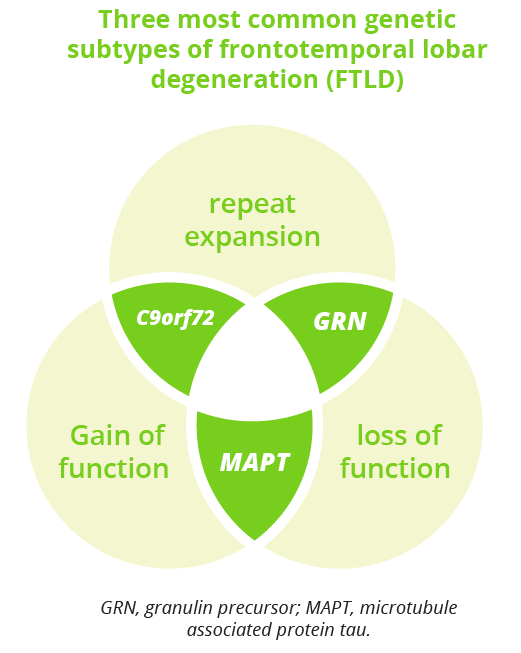

What are the three most common genetic subtypes of FLTD?

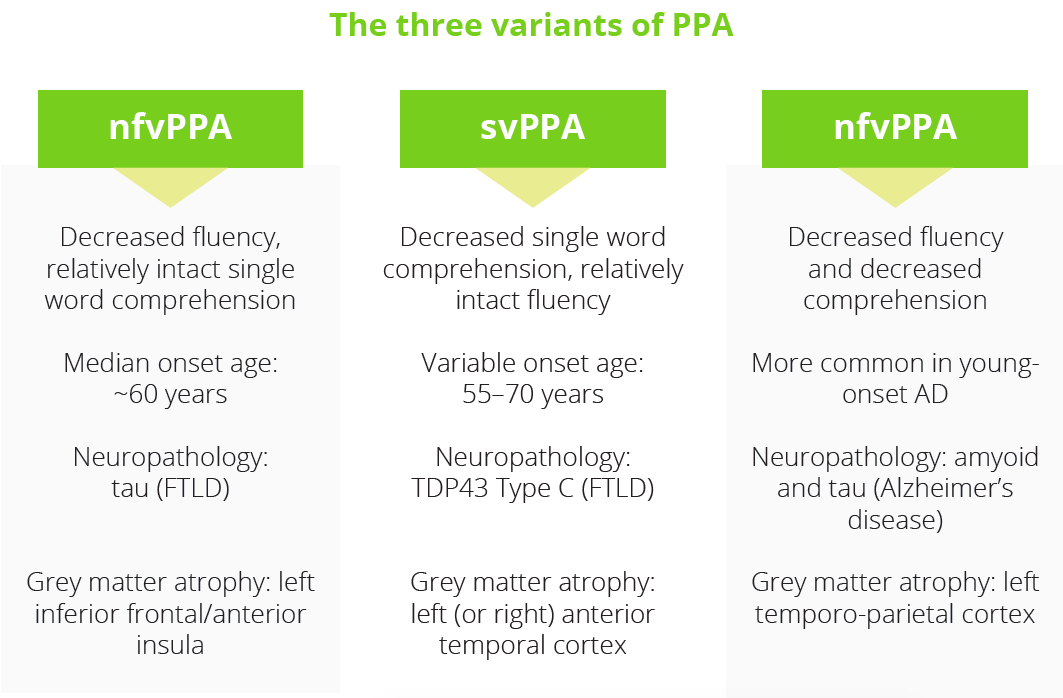

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) incorporates three clinical syndromes which involve language impairments selectively or primarily early on: non-fluent variant (nfvPPA), semantic variant (svPPA) and logopenic variant (lvPPA). Carmela Tartaglia, Toronto, Canada, outlined the key clinical features and neuropathology of each type of PPA and explained that ‘anatomy dictates signs and symptoms’. Given the heterogeneity of the clinical phenotype, it is important for physicians to adapt the neurological assessment to each patient’s individual situation. For managing PPA, Dr Tartaglia recommended prioritising education over medication where possible. Currently there are no pharmacological treatments able to cure or delay the progression of PPA, but symptomatic options are available and protein-specific treatments are on the near horizon.

“For the first time in the field (of FTD) we have a plethora of clinical studies that are looking for patients to test either disease-modifying therapies or symptomatic therapies.”

Elizabeth Finger, London, Canada

PPA incorporates three clinical syndromes which involve language impairments selectively or primarily early on: non-fluent variant (nfvPPA), semantic variant (svPPA) and logopenic variant (lvPPA). Carmela Tartaglia, Toronto, Canada, outlined the key clinical features and neuropathology of each type of PPA and explained that ‘anatomy dictates signs and symptoms’. Given the heterogeneity of the clinical phenotype, it is important for physicians to adapt the neurological assessment to each patient’s individual situation. For managing PPA, Dr Tartaglia recommended prioritising education over medication where possible. Currently there are no pharmacological treatments able to cure or delay the progression of PPA, but symptomatic options are available and protein-specific treatments are on the near horizon.

What are the three variants of PPA?

Recommended approaches in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease

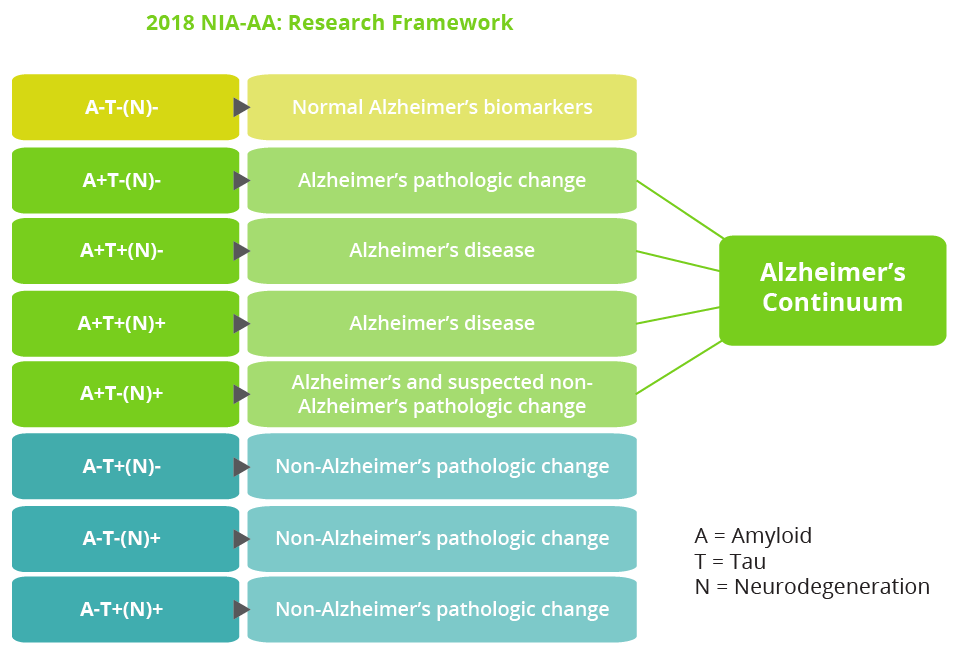

An educational seminar delivered by Liana Apostolova, Indiana, USA, focused on current knowledge and recommended approaches in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). AD is a dual proteinopathy in which amyloid-β plaques and neurofibrillary tangles represent the fundamental pathological changes. Alongside neurodegeneration, the two proteins amyloid and tau make up the key criteria that define the Alzheimer’s continuum according to the 2018 National Institute on Aging—Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) Research Framework.

The 2018 NIA-AA Research Framework includes an Alzheimer’s continuum

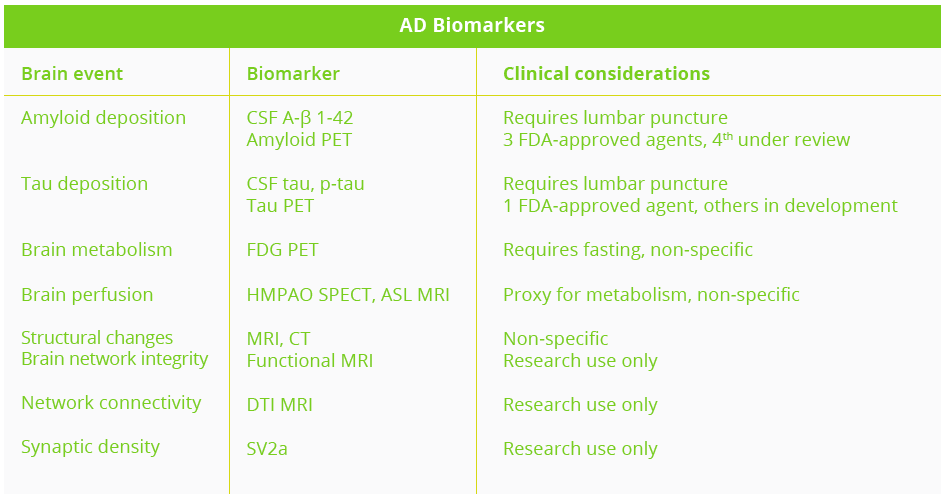

Several other AD biomarkers exist, however Dr Apostolova stressed that ‘we still need more’. The primary goal of the Longitudinal Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease (LEADS) observational study is to develop sensitive clinical and biomarker measures for future clinical and research use in AD.

Clinical considerations of AD biomarkers

ASL, arterial spin labelling; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computerised tomography; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; HMPAO, hexamethyl propylenamine oxime; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; SPECT, single photon emission computed tomography; SV2a, synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2a

AD biomarkers can play several critical roles - aiding in early pre-symptomatic detection through screening, ensuring clinical diagnosis with maximum sensitivity and specificity, and helping with prognostication via disease staging and outcome prediction. Biomarkers are also critical for the identification of atypical AD variants such as posterior cortical atrophy, logopenic aphasia and frontal variant AD which are commonly misdiagnosed.

“In recent decades we have moved away from the purely clinical AD taxonomy to one that conceptualises AD as a clinicopathologic entity.”

Liana Apostolova, Indiana, USA

Controversies in Neurology

In a scholarly debate, Jeffrey Cummings, Nevada, USA, argued in favour of amyloid as a target for AD drug development, noting that amyloid is central to the neuropathological diagnosis of AD and genetic evidence provides strong support for the primacy of amyloid-β. AD animal models and biomarkers also show that amyloid-β precedes other pathologies of AD. Although acknowledging that anti-amyloid clinical trials have thus far proved negative, Dr Cummings insisted that key learnings have been accrued and current drug development approaches with monoclonal antibodies appear more promising.

“Current trials of anti-amyloid β monoclonal antibodies support a relationship between amyloid lowering and clinical benefit.”

Jeffrey Cummings, Nevada, USA

Mary Santo, New York, USA, countered that continuing to target amyloid would simply be ‘treating a tautology’ and not serving the needs of all persons with cognitive impairment and dementia, most notably those with AD-related disorders. Symptom improvement rather that amyloid plaque removal should be the goal of treatment said Dr Santo, especially given that at least three separate clinical studies have shown little or no benefit on clinical outcomes despite successful amyloid removal. She suggested that more fruitful targets to pursue in AD could include neurodegeneration and apolipoprotein ε4.

Lewy body dementias

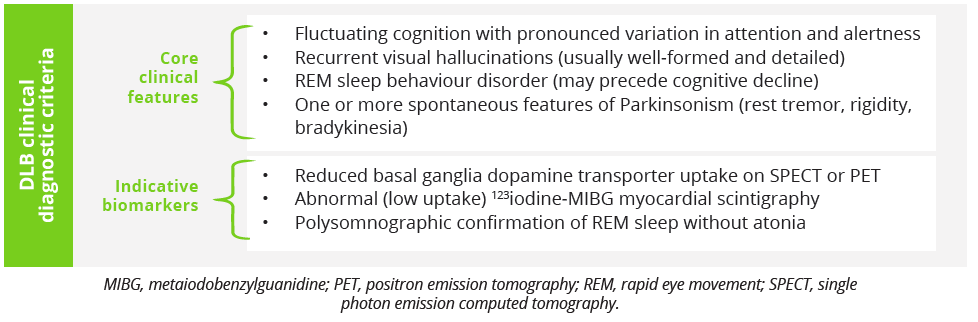

An update on dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) was provided by Melissa Armstrong, Gainsville, USA. Dr Armstrong explained that DLB is defined diagnostically as dementia occurring before or concurrently with Parkinsonism, but shows significant overlap in both clinical symptoms and prodromal features with Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy (MSA).

A probable DLB diagnosis requires two or more clinical features with or without indicative biomarkers, or one core clinical feature and one or more indicative biomarkers. In 2020, new research criteria for the diagnosis of prodromal DLB was published which identified three different presentations: mild cognitive impairment (MCI) onset, delirium-onset and psychiatric-onset. Currently, there are no FDA-approved therapies specifically for DLB and management is centred on the relief of Parkinsonism with carbidopa/levodopa. Non-pharmacological approaches include therapy, exercise and social support. Looking at disease natural history, Dr Armstrong highlighted that median time from clinical diagnosis to death in patients with DLB is just 3–4 years, with over 70% of deaths due directly to the underlying dementia or failure to thrive according to a US survey of 658 caregivers/family members. End of life expectations and experiences are therefore important conversations to have with patients and their families, she stressed.

DLB clinical diagnostic criteria

Closing Remarks

Hailing this year’s annual meeting as ‘ANN excellence delivered unconventionally’ outgoing President Dr Stevens closed the congress by handing the reins of leadership to the new ANN President Dr Avitzur with the passing of the gavel. Dr Avitzur expressed her hope for an optimistic future with next year’s AAN meeting, due to take place in Seattle, Washington, between the 2nd and 8th April 2022, providing the opportunity for members to come back together again in person.

©Springer Healthcare 2021. This content has been independently selected and developed by Springer Healthcare and licensed by Roche for Medically. The topics covered are based on therapeutic areas specified by Roche. This content is not intended for use by healthcare professionals in the UK, US or Australia. Inclusion or exclusion of any product does not imply its use is either advocated or rejected. Use of trade names is for product identification only and does not imply endorsement. Opinions expressed do not reflect the views of Springer Healthcare. Springer Healthcare assumes no responsibility for any injury or damage to persons or property arising out of, or related to, any use of the material or to any errors or omissions. Please consult the latest prescribing information from the manufacturer for any products mentioned in this material.