Retinal Disease Hub: Macular Degeneration

Understanding retinal disease

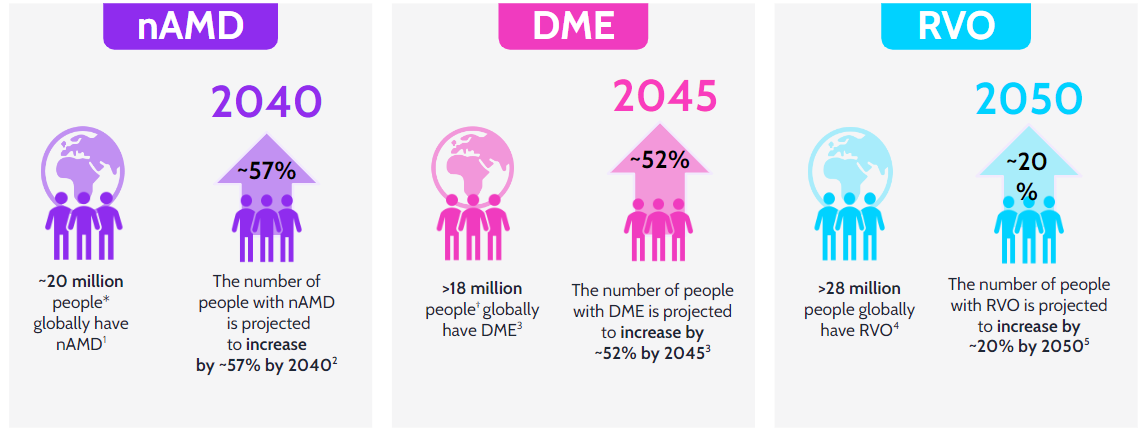

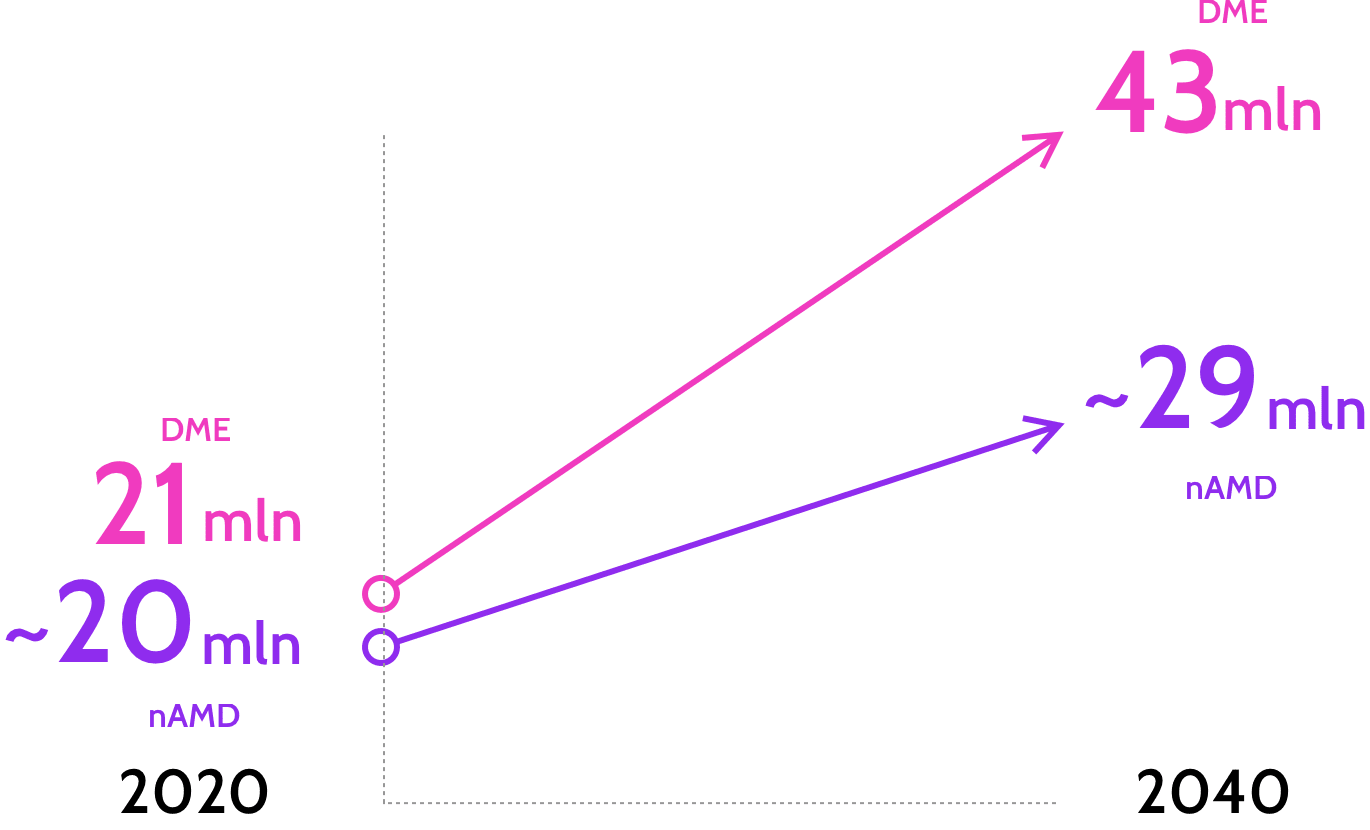

Retinal diseases remain a leading cause of vision loss with increasing global prevalence29-33

The reality of retinal disease

Retinal disease is a significant public health issue that is now affecting more of us than ever before. The number of people living with two of the leading causes of vision loss - Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration (nAMD) and Diabetic Macular Edema (DME) - worldwide is set to grow,5-13 further increasing the pressure on health system capacity.

Projected number of people living with retinal disease5-10

These diseases can have a devastating impact upon our work, our health systems, and those we care about most by closing the window to independence.

People may struggle to:14-18

The Expensive Consequences of Retinal Disease

Those living with vision loss and impairment (and often their loved ones too), must also manage the financial costs of: 14,15

- Take time off work

- Organise informal care

- Travel to and from appointments

Although anti-VEGF therapies have redefined the care of patients with retinal diseases, new treatments are still required to reduce treatment burden

References:

- Mayo Clinic. Retinal diseases. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/retinal-diseases/symptoms-causes/syc-20355825 [last accessed June 2022]

- Genentech. Age-related macular degeneration. https://www.gene.com/patients/disease-education/age-related-macular-degeneration [last accessed June 2022]

- NEI. Diabetic retinopathy. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/diabetic-retinopathy [last accessed June 2022]

- ASRS. Branch retinal vein occlusion. https://www.asrs.org/patients/retinal-diseases/24/branch-retinal-vein-occlusion [last accessed June 2022]

- Yau J, Rogers S, Kawasaki R, et al. Global Prevalence and Major Risk Factors of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:556–64.

- Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Elsevier. 2017;128:40-50.

- Cheloni R, Gandolfi SA, Signorelli C, et al. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e022188. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022188.

- Connolly E, Rhatigan M, O’Halloran AM, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration associated genetic risk factors and 4-year progression data in the Irish population. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:1691–95.

- Bright Focus Foundation; Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Facts & Figures, 2019. Available from: www.brightfocus.org/macular/article/age-related-macular-facts-figures [Accessed December 2021].

- Wong WL, Su X, Li X et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2014; 2(2): e106-e116.

- Macon C, Carrier H, Janczewski A, et al. Effect of Automobile Travel Time Between Patients’ Homes and Ophthalmologists’ Offices on Screening for Diabetic Retinopathy. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24(1):11-20.

- Rose MA, Vukicevic M, Koklanis K, et al. Experiences and perceptions of patients undergoing treatment and quality of life impact of diabetic macular edema: a systematic review. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(4):383-401.

- Elshout M, Webers CA, Van Der Reis MI, et al. Tracing the natural course of visual acuity and quality of life in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A systematic review and quality of life study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17(1):120.

- Xu K, Gupta V, Bae S, Sharma S. Metamorphopsia and vision-related quality of life among patients with age-related macular degeneration. Can J Ophthalmol. 2018;53(2):168-72.

- Bian W, Wan J, Smith G, et al. Domains of health-related quality of life in age-related macular degeneration: a qualitative study in the Chinese cultural context. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e018756.

- Prem SM, Khadka J, Gilhotra JS, et al. Exploring the quality of life issues in people with retinal diseases: a qualitative study. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;1(1):15.

- Dev MK, Paudel N, Joshi ND, et al. Impact of visual impairment on vision-specific quality of life among older adults living in nursing home. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39(3):232-8.

- Monés J, Singh RP, Bandello F, et al. Undertreatment of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration after 10 Years of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy in the Real World: The Need for A Change of Mindset. Ophthalmologica. 2020;243(1):1-8.

- Holekamp NM et al. Barriers to adherence to age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema management plans: A multi-national qualitative study. Presented at ARVO 2021. May 1-7, 2021.

- Sivaprasad S and Oyetunde S. Impact of injection therapy on retinal patients with diabetic macular edema or retinal vein occlusion. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:939-46.

- Spooner KL et al. The burden of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a patient's perspective. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:2483–91.

- Boulanger-Scemama E, et al. Ranibizumab for exudative age-related macular degeneration: A five year study of adherence to follow-up in a real-life setting. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2015;38:620–7.

- Obeid A, et al. Loss to Follow-up Among Patients With Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Who Received Intravitreal Anti–Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Injections. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:1251–9.

- Gillies MC, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Treatment of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Data from an Observational Study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1837–45.

- Glassman AR et al. Ophthalmology 2020;127(9):1201-10.

- Adamis, Anthony P et al. Building on the success of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy: a vision for the next decade. Eye. 2020;34(11):1966-72.

- Chakravarthy U, Yang Y, Lotery A, et al. Clinical Evidence Of The Multifactorial Nature Of Diabetic Macular Edema. Retina. 2018;38(2):343-51.

- Joussen AM, Ricci F, Paris LP, et al. Angiopoietin/tie2 signalling and its role in retinal and choroidal vascular diseases: A review of preclinical data. Eye (Lond) 2021;35:1305–16.

- Hayashi-Mercado R, et al. Int J Retin Vitr. 2022;8:29.

- Wong WL, et al. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e106–16.

- Teo ZL, et al. Ophthalmol. 2021;128:1580–91.

- Song P, et al. J Glob Health. 2019;9:010427.

- Li JQ, et al. Ophthalmologica. 2019;241:183–9.