CUP Syndrome (Cancer of Unknown Primary)

INTRODUCTION

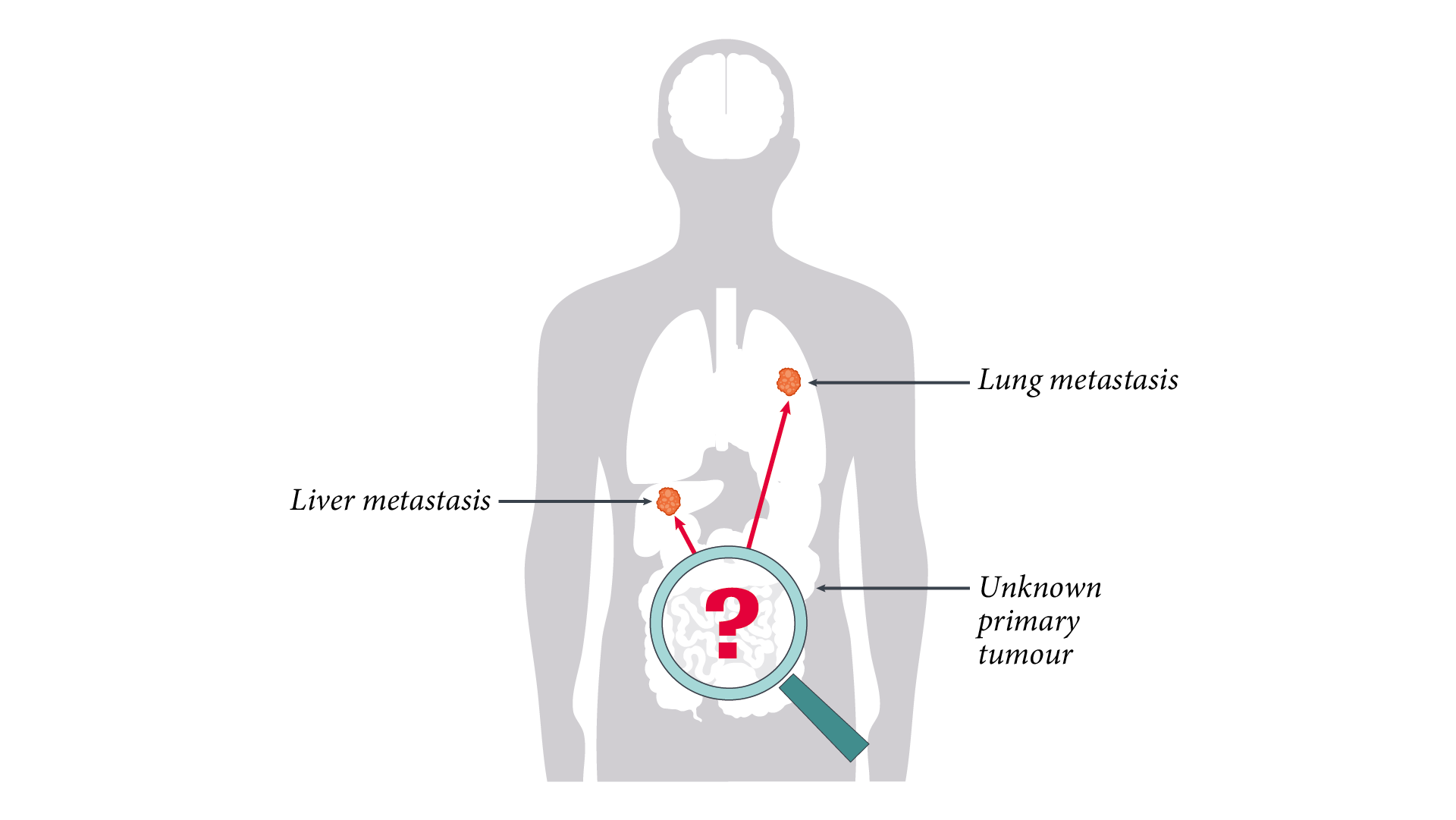

CUP (cancer of unknown primary) syndrome is defined as a histologically and clinically verified cancer for which only metastases can be found at the time of diagnosis, but no primary tumour is detectable.

1. Krämer A et al., Annals of Oncology 2022/ https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(22)04769-X/fulltext

2. Stella GM et al. J Transl Med 2012; 10: 12.

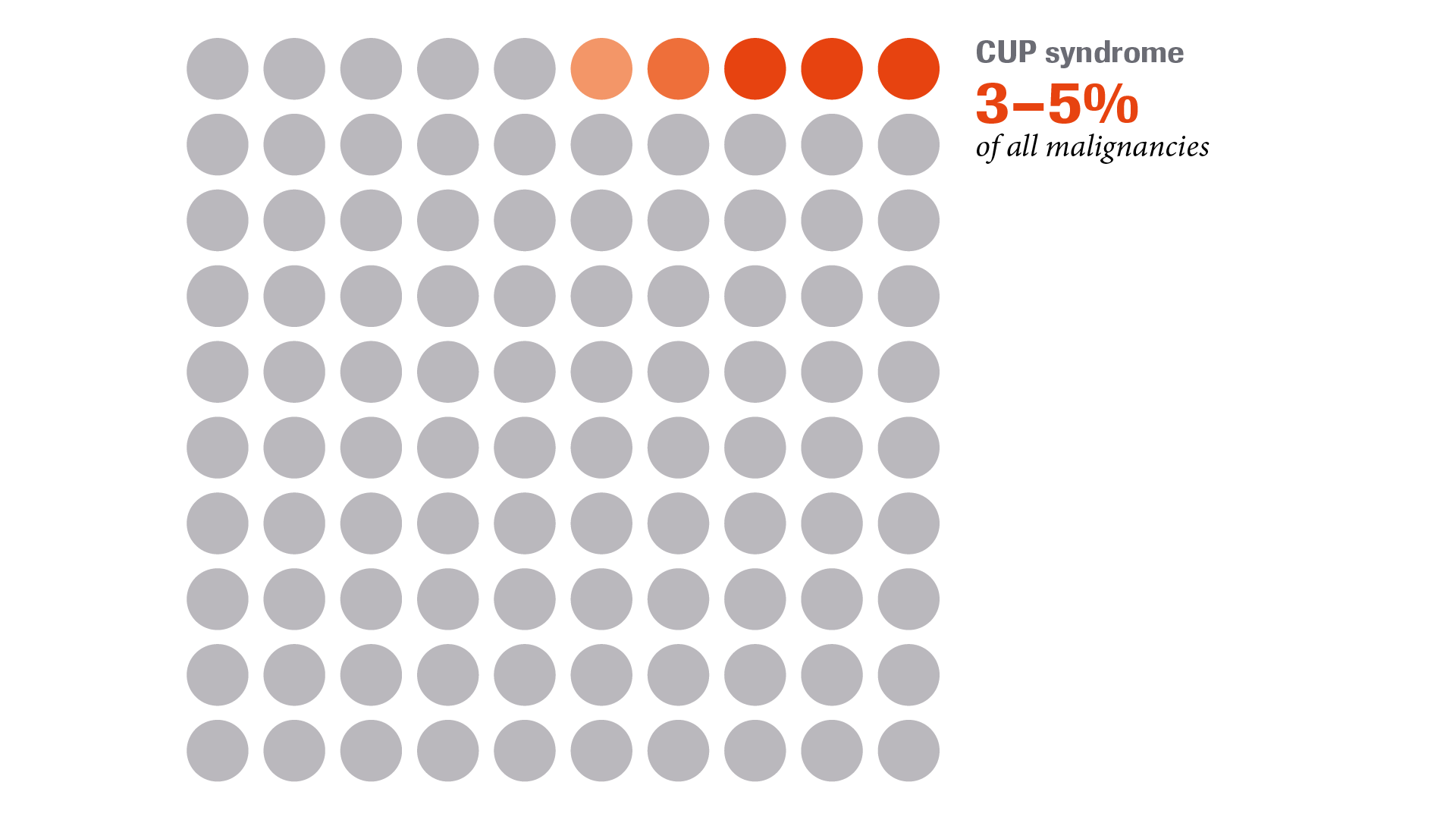

CUP syndrome accounts for approximately 3–5% of all cancer cases.

1. Krämer A et al., Annals of Oncology 2022/ https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(22)04769-X/fulltext

2. Stella GM et al. J Transl Med 2012; 10: 12.

PATHOGENESIS

How might CUP develop?

There are various hypotheses on aetiology and pathogenesis. One tentative explanation for CUP is the “stem cell theory” of cancer.1-3 Asynchronous division of the premalignantly or malignantly transformed stem cells may produce daughter cells that do not grow locally but are able to metastasise. Given the favourable microenvironment of these metastases, these may spread to another site, even though no tumour develops in the tissue of origin.4 This hypothesis is supported by tumour genomics, with clonal evolution documented in various cancers (e.g., lung cancer).5

1. Aktipis CA et al. Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 13: 883–92.

2. Visvader JE. Nature 2011; 469: 314–22.

3. Lee G et al. J Stem Cell Res Ther 2016; 6: 363.

4. López-Lázaro M. Oncoscience 2015; 2: 467–75.

.png)

RISK FACTORS

What are the potential risk factors for CUP?

Potential risk factors that support the development of CUP syndrome include:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Smoking

- Obesity

- A positive family history of cancer

1. Mnatsakanyan E et al. Cancer causes & control 2014; 25: 747–57.

2. Robert Koch Institut (2016) GEKID Publication. Available at: www.gekid.de (last accessed March 2019).

3. Hemminki K et al. Int J Cancer 2015; 136: 246–47.

CLINICAL FEATURES

-

What are the clinical features of CUP syndrome?

CUP syndrome presents a complex disease picture. A variety of heterogeneous manifestations can be distinguished but none have been identified as exclusively specific to CUP syndrome.1-3 -

How is CUP syndrome categorised?

CUP has different subsets, identification of which can imply a specific treatment. Based on histology, there are 5 different subsets.4-6

1. Cancer.net. Unknown Primary: Symptoms and Signs. Available at: www.cancer.net/cancer-types/unknown-primary/symptoms-and-signs (last accessed March 2019).

2. Mayo Clinic Carcinoma of unknown primary. Available at: www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/carcinoma-unknown-primary/symptoms-causes/syc-20370683 (last accessed March 2019).

3. The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Cancer of Unknown Primary. Available at: www.mdanderson.org/cancer-types/cancer-of-unknown-primary.html (last accessed March 2019).

4. Stella GM et al. J Transl Med 2012; 10: 12.

5. Pavlidis N and Pentheroudakis G. Lancet 2012; 379: 1428–35.

6. Ettinger DS et al. NCCN Guidelines version 2.2019.

DIAGNOSIS

-

How is CUP diagnosed?

The heterogeneity of CUP syndrome makes diagnosis challenging. Although the prognosis for CUP patients is generally poor, the appropriate diagnostic work-up can help to identify patients who can have a favourable prognosis. This subset of patients receives a therapy according to the suggested site of tumour origin.1 -

What do guidelines recommend for CUP diagnosis?

The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommends the following diagnostic work-up for suspected CUP patients:1

-

What is the role of molecular tumour profiling in CUP?

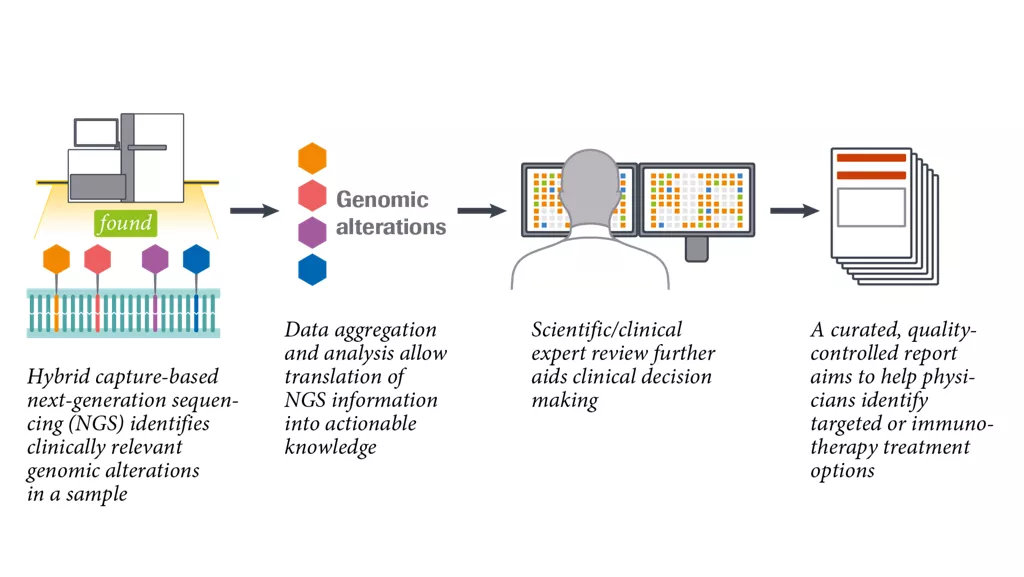

Molecular tumour profiling techniques, such as comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) make it possible to identify clinically relevant alterations in CUP. Based on next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, CGP detects both known and novel variants across the four main classes of genomic alterations in a large subset of cancer-related genes and identifies genomic signatures, i.e. tumour mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI).2-7 -

Clinical practice example of CUP

A 53-year-old female patient presented with shortness of breath and a golf ball-sized subcutaneous mass in the right biceps with erythema of the overlying skin. PET and CT showed multiple metabolically active masses in both lungs.

Rather than subject the patient to the risk of a lung biopsy, it was decided to biopsy the skin lesion on the arm and perform CGP. Instead of the suspected lung cancer, CGP identified an EML4-ALK fusion alteration.8

- Krämer A et al., Annals of Oncology 2022/ https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(22)04769-X/fulltext

- Frampton GM et al. Nat biotechnol 2013; 31: 1023–31.

- He J et al. Blood 2016; 127: 3004–14.

- Gagan J and van Allen EM. Genome Med 2015; 7: 80.

- Rozenblum AB et al. J Thorac Oncol 2017; 12: 258–68.

- Suh JH et al. Oncologist 2016; 21: 684–91.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology.

Non-Small Lung Cancer. V.2.2019. Available at:

www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/recently_updated.aspx

(last accessed March 2019). - Chung J et al. Case Report Oncol 2014; 7: 628–82.

PROGNOSIS

-

What is the prognosis for CUP patients?

Only 15–20% of patients with CUP have a favourable prognosis based on their clinicopathological classification. These patients have chemosensitive and potentially curable tumours and can achieve long-term disease control with a multidisciplinary approach.1

The majority of CUP patients (80–85%) have a poor prognosis, meaning that treatment response is poor and median overall survival is generally less than one year.1

-

Survival rate of CUP patients of poor-prognosis subset

The survival rates for patients with poor prognosis are low:2

- 1 year: 38%

- 5 years: 10%

- 10 years: 8%

1. Krämer A et al., Annals of Oncology 2022/ https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(22)04769-X/fulltext

2. Greco FA and Hainsworth JD (2011) Cancer of unknown primary site, DeVita VT Jr., Hellman S, Rosenberg SA (eds) Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology (9th ed) Philadelphia, PA, JB Lippincott: 2033–51.

TREATMENT

-

How is CUP clinically managed?

Treatment should be tailored to the individual patient according to the clinicopathological characteristics and its subsequent prognostic classification. The 15–20% of CUP patients with a favourable prognosis should be treated similarly to patients with metastases from equivalent known primary tumours. Patients with unfavourable risk profiles currently have a poor prognosis despite treatment with different chemotherapy combinations in clinical trials.1

The figure shows a proposal for clinical management of patients with CUP, including assignment to defined subsets, exclusion of non-CUP neoplasms and the use of prognostic parameters:1

-

Evolving treatment options for CUP patients

In recent years platinum-based chemotherapy has been supplemented by two additional options.2-9

1. Fizazi K et al. Ann Oncol 2015; (26 suppl 5): v133–8.

2. Hainsworth JD and Greco FA. ASCO educational book 2018.

3. Moran S et al. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 1386–95.

4. Greco FA et al. Ann Oncol 2012; 23: 298–304.

5. Ross JS et al. JAMA Oncol 2015; 1: 40–9.

6. Subbiah IM et al. Oncoscience 2017; 4: 47–56.

7. Varghese AM et al. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: 3015–21.

8. Kato S et al. Cancer Res 2017; 77: 4238–46.

9. Krämer A et al. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 15_suppl e24162.