Pemphigus vulgaris (PV)

Clinical manifestations of PV

Pemphigus, derived from the Greek word ‘pemphix’ meaning blister or bubble, is a group of rare autoimmune blistering diseases characterized by intraepithelial blisters on the skin and mucous membranes.1

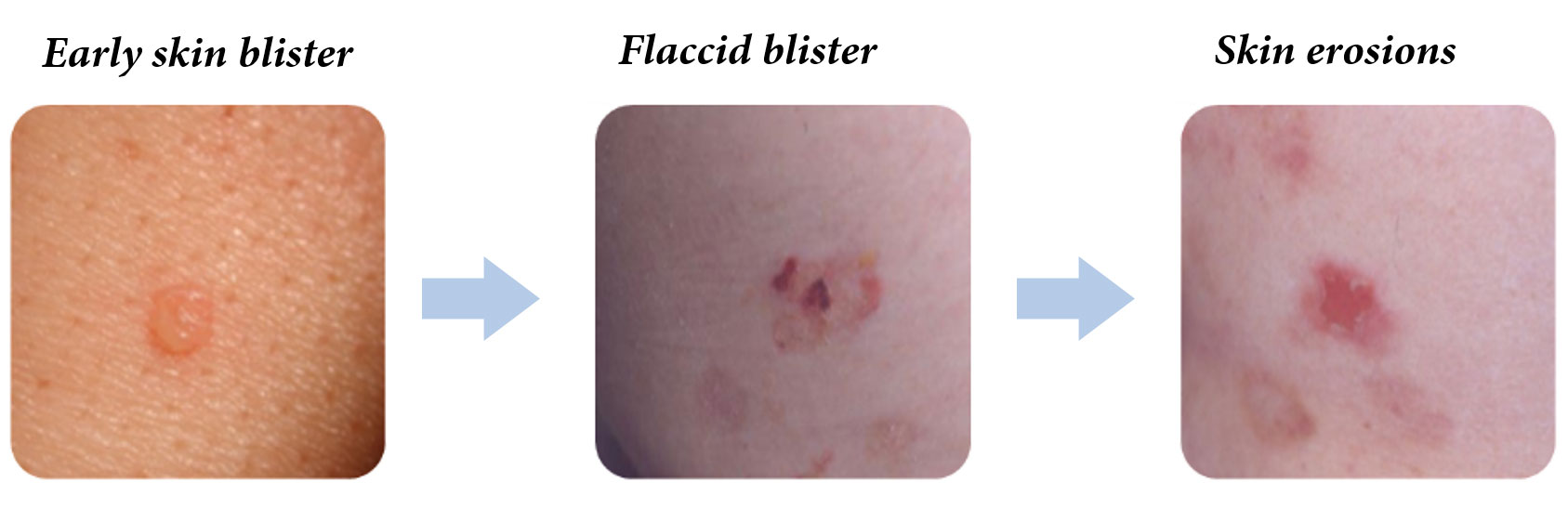

PV usually manifests as painful lesions of the oral mucosa, which can be buccal and/or gingival, and can interfere with eating if they are persistent.2 Cutaneous involvement can appear several weeks or months after the first appearance of mucosal lesions and presents as flaccid bullae containing a clear fluid on non-erythematous skin that quickly transform into post-bullous erosions.2

Prevalence and epidemiology

PV is the most common subtype of pemphigus in Europe, the United States and Japan,1 accounting for around 70% of pemphigus cases.3 The incidence of PV varies globally, ranging from 0.5–50 new cases per million people.1 Epidemiology studies in Europe indicate that PV incidence tends to be lower at higher latitudes, with incidence ranging from 0.5 cases per million Germany to 8 cases per million in Greece.1 PV occurs slightly more frequently in women than men.4 PV affects all races but is more prevalent in people of Mediterranean or Jewish ancestry.4,5 PV is typically diagnosed between the ages of 50–60 years,4 but age of onset varies globally.

Morbidity and mortality

PV is a serious condition that is associated with significant morbidity and a high risk of mortality. PV has been associated with a 3-fold increased risk of death compared with the general population and had a 1-year mortality rate of 12% (8–19%) in a UK population.6

PV is caused by the development of immunoglobulin G (IgG) auto-antibodies to desmogleins, desmosomal transmembrane proteins involved in maintaining the structure of the skin and mucosa. Anti-desmoglein 1 and/or anti-desmoglein 3 antibodies drive the loss of cell-cell adhesions between keratinocytes, resulting in severe blisters and erosions on the skin and/or mucous membranes.1

Signs and symptoms of PV

PV is characterized by the development of blisters (bullae) on the skin and mucosal membranes, primarily in the mouth, but PV may also affect the lining of the nose, throat and genitals.

The blisters that develop in PV are flaccid in nature making them fragile and prone to rupturing. The blisters rupture quickly, particularly in the mouth, resulting in painful lesions or erosions that may spread due to continued shedding of the epithelium.1

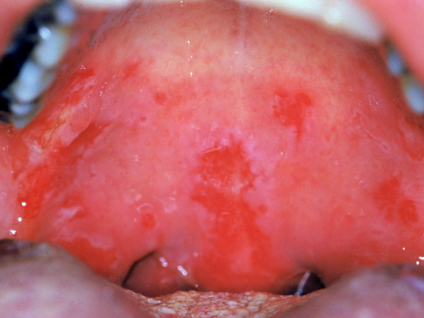

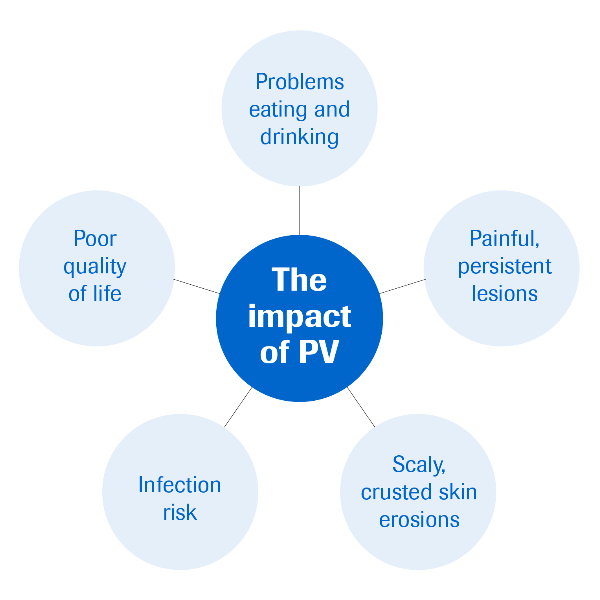

In the majority (50–70%) of cases, the first sign of PV is the development of blisters in the mouth, commonly on the inside of the cheeks. Inflammation of the mouth and lips (stomatitis) may also indicate the onset of PV. Patients may have difficulty swallowing due to persistent and painful lesions which are slow to heal. Over time this may lead to weight loss and malnutrition.1

Although PV usually manifests first as painful lesions in the mouth, other mucosal membranes may be less commonly affected; these include the conjunctiva, in the form of non-cicatricial ocular lesions, and erosions of the nasal, laryngeal, esophageal and rectal mucosa.2

PV may be limited to the mucosal membranes in the mucosal-dominant subtype, or skin lesions may also develop after an average of 5 months (mucocutaneous subtype). Flaccid blisters develop on otherwise healthy-looking or erythematous skin typically on the chest, scalp, face or between the shoulder blades. Skin lesions are often painful but are not usually itchy.2 Skin erosions may appear partly crusted due to abnormal growth of keratinocytes with a granular papillomatous (nipple or frond-like) appearance, especially where the skin folds.1 Blisters and erosions may be limited to the skin (cutaneous subtype); however, this type of PV is less common than those involving the mucosal membranes.1

Oral lesions

Images reproduced with permission from Medscape Drugs & Diseases (https://emedicine.medscape.com/), Pemphigus Vulgaris, 2018, available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1064187-overview.

Progression of PV and risk of secondary infections

PV is a chronic disease that if left untreated can quickly progress to severe disease with multiple erosions that are susceptible to infections and dehydration.2,10 Secondary infections occurring in PV patients may lead to sepsis and cardiac failure and PV is, therefore, considered to be a life-threatening disease.2 PV patients are reported to have a 3-times higher risk of mortality than the general population.9

Impact of PV symptoms on quality of life and mental health

PV symptoms can have a considerable impact on patient’s quality of life8,9 with a high proportion of PV patients reporting a negative impact on their mental health.10

It can be challenging to identify PV as the lesions can resemble other clinically similar disorders where skin and mucosal blisters develop.1 Patients with persistent erosive oral lesions or skin blisters should be further investigated for PV.

The International Pemphigus and Pemphigoid Foundation (IPPF) is a nonprofit organization seeking to improve the quality of life for all people affected by pemphigus and pemphigoid through early diagnosis and support. Visit the IPPF website for additional clinical information about PV.

References

- Kasperkiewicz M, et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017; 3:17026.

- Hertl M, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015; 29:405-414.

- Martin LK, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; Cd006263.

- Alpsoy E, et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015; 307:291-298

- Simon DG, et al. Arch Dermatol. 1980; 116:1035-1037.

- Langan SM, et al. BMJ. 2008; 337:a180.

- Kridin K, et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017; 97:607-611.

- Penha MA, et al. An Bras Dermatol. 2015; 90:190-194.

- Rajan B, et al. Perm J. 2014; 18:e123-127.

- Arbabi M, et al. Indian J Dermatol. 2011; 56:541-545.