Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Prognosis, Cure & Therapies

Early diagnosis provides the best outcomes1-4

Curative therapies for HCC present the best choice for long term survival, but are only available for early disease stages4

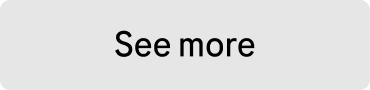

The prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is associated strongly with disease staging.2 Identification of tumors at an early stage is critical, as curative treatments exist and provide the best opportunity for long-term survival.4

However, HCC diagnosis is often delayed due to lack of symptoms and awareness,5,6 significantly worsening prognosis, limiting available treatment options,1,3 and reducing patient survival outcomes.1-4

Early stages

Very early stage (0)

Patients with very early stage disease may not have any cancer-related symptoms.2,7 If identified and treated at this stage, survival is expected to extend beyond 5 years.2

Management of very early stage disease should consider liver transplantation as a standard of care due to the high risk of disease recurrence.2 If liver transplantation is not feasible, the other treatment approaches may include resection or thermal ablation,2,7 which is associated with similar survival outcomes to resection.2

Early stage (A)

Patients with early stage disease have a similar initial presentation as those with very early disease and without any cancer-related symptoms.2,7 Survival is expected to extend beyond 5 years with early treatment and no high-risk tumor features.2

Treatment recommendations are defined by the presence of either a single cancer, or the presence of several small cancers (≤3 nodules each ≤3 cm), without extrahepatic spread.2 If transplantation is not feasible, patients should be evaluated for ablation or resection with curative intent.2

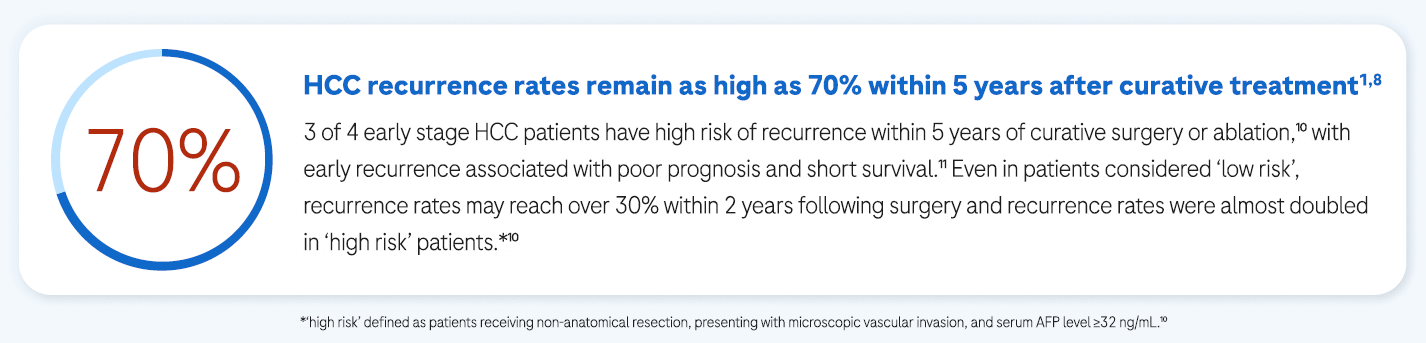

There is an urgent need of adjuvant treatment options to address the high recurrence risk1,8,9

Currently, there is no recognised consensus on ‘high risk’ criteria for HCC recurrence, and MDTs/HCPs must use their own clinical judgment to identify such patients. Some suggested ‘high risk’ criteria for HCC recurrence have included:

Up to three tumors, with the largest >5 cm (following resection) 9

Multifocal disease (≥3 nodules)2,4,9,12

Poor tumor differentiation (defined as Grade 3 or 4) 9

Vascular invasion4,9,12

Adjuvant therapy could help reduce the risk of recurrence after curative surgery or ablation

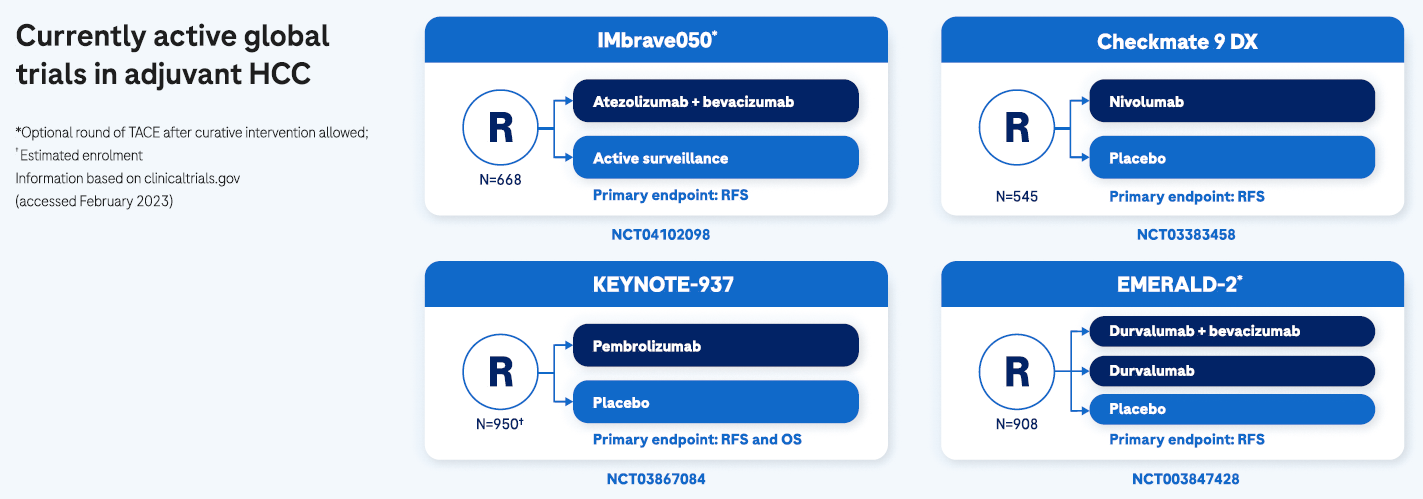

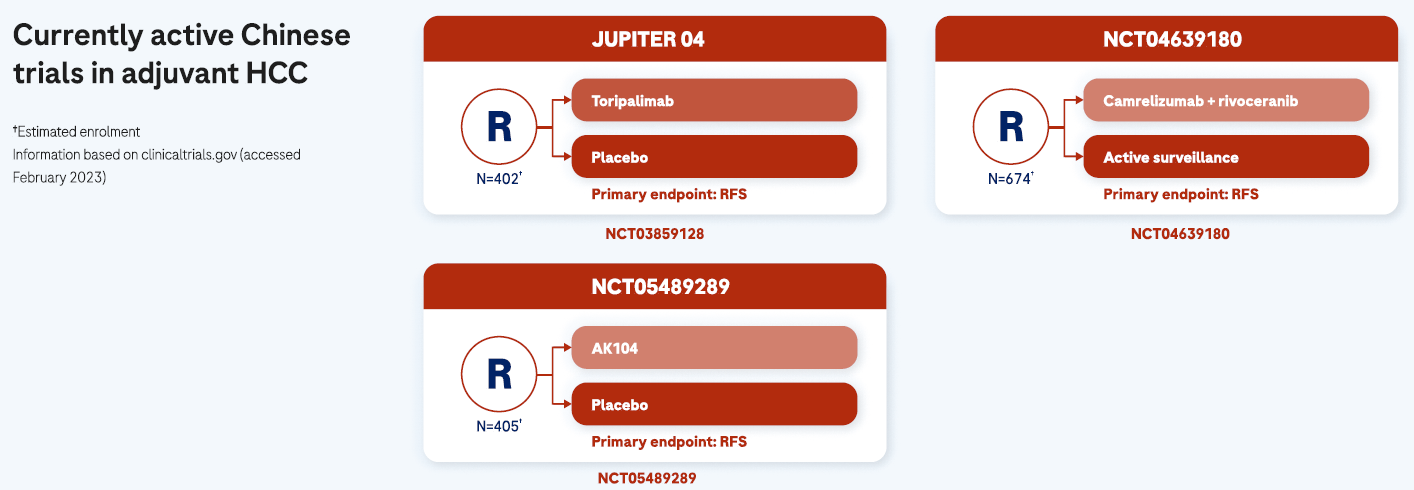

The availability of adjuvant treatment options following curative interventions are urgently needed to reduce the recurrence risk and improve opportunities for long-term cure, especially for patients at high risk of early HCC recurrence.9 Although several phase III trials with newer immunotherapy agents in the adjuvant setting are ongoing,1 there are no approved adjuvant treatment options available and HCC recurrence remains an area of unmet need.9

Intermediate stages

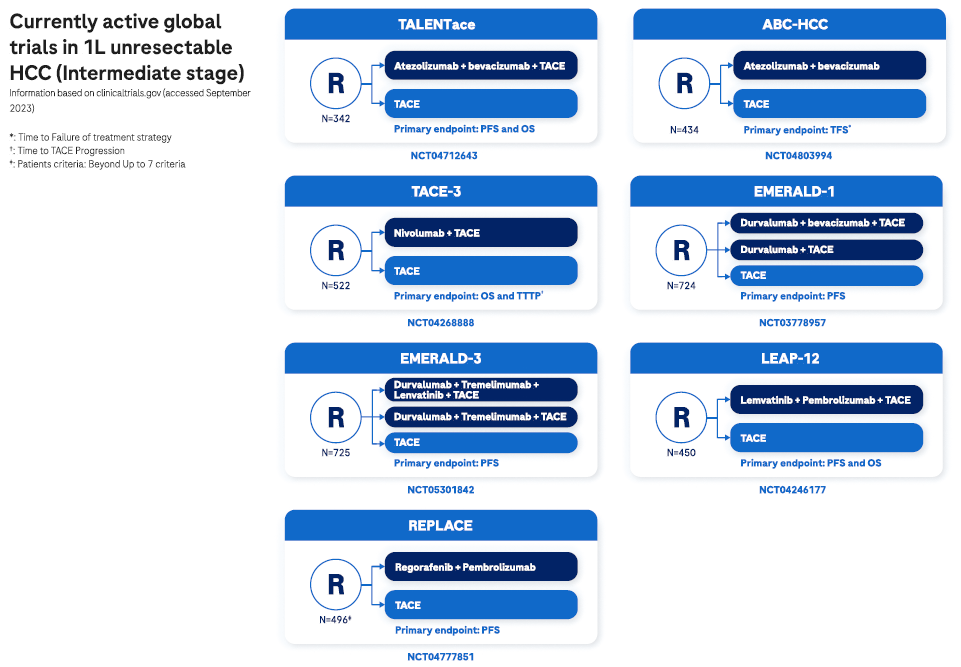

Intermediate HCC presents in patients without any cancer-related symptoms2,7 and comprises multiple nodules without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread. At this disease stage, tumor burden may be quite heterogeneous and influences available management options.2

Patients with well-defined HCC nodules may be candidates for liver transplantation or locoregional therapy (such as transarterial chemoembolization). Patients with diffuse, infiltrative, and extensive HCC liver involvement do not benefit from TACE, and systemic therapy should be the recommended option.2

Expected survival is dependent on available treatment options, ranging from >5 years with transplantation, >2.5 years following TACE, or >2 years with systemic treatment.2

Advanced stages

Patients with advanced HCC tend to be relatively fit with preserved liver function.2 Symptoms tend to be vague and can include fatigue, unexplained weight loss, nausea, disturbed sleep, altered bowel function, and jaundice.13,14 HCC is an aggressive cancer and, when diagnosed at an advanced stage, curative treatment become unavailable and systemic management options are limited 1,4

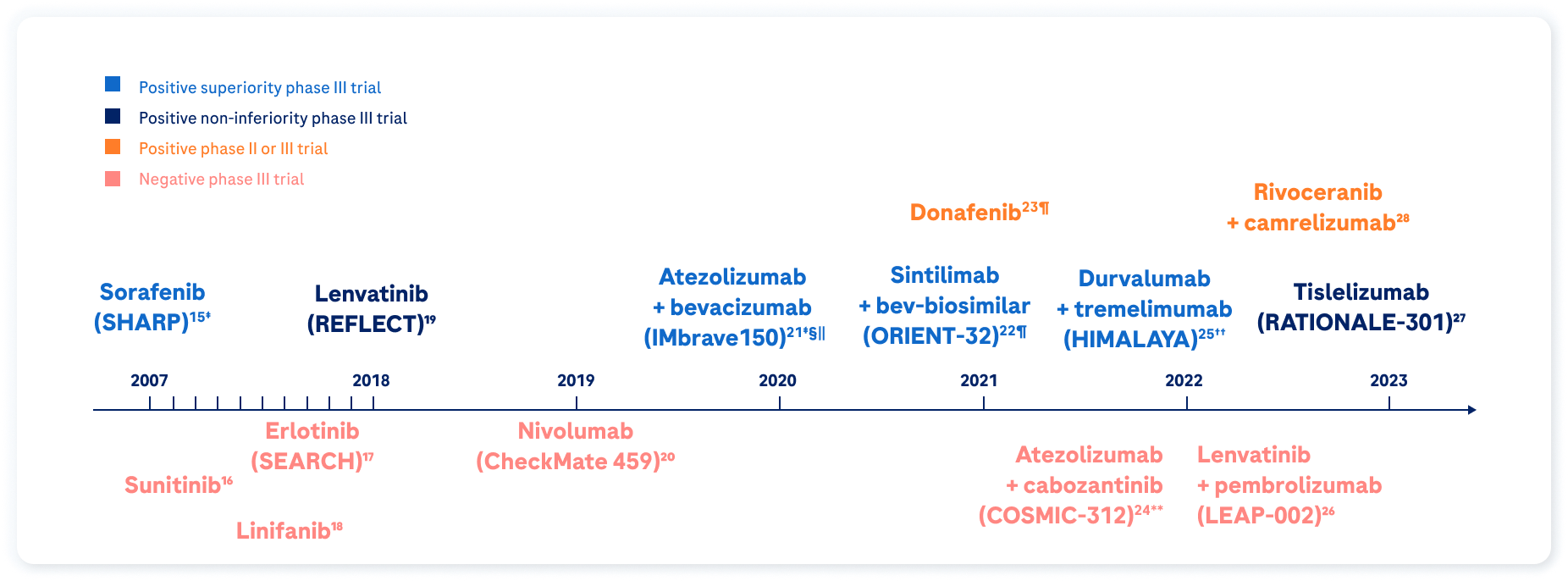

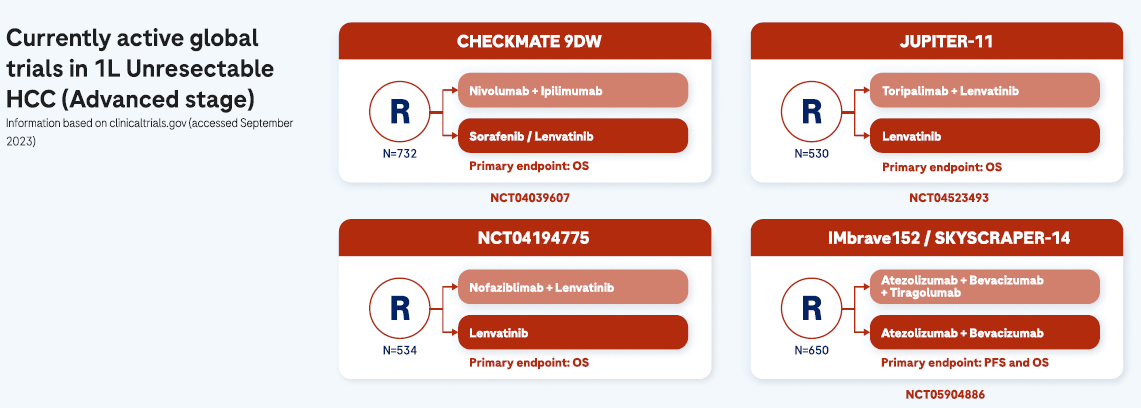

Progress has been made in 1L systemic treatment of HCC in recent years

* Optional round of TACE after curative intervention allowed.

† Estimated enrolment.

‡ The use of this product has EMA authorisation and funding conditions from the HNS.

§The atezolizumab indication in combination with bevacizumab is funded by the HNS for the treatment of adult patients with advanced or unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma who have not received prior systemic therapy, with liver function (Child-Pugh stage A), an ECOG score of 0 or 1, in the absence of untreated or undertreated esophagogastric varices and in the absence of autoimmune diseases.

‖The reflected information refers to the bevacizumab data sheet; in case of administering another bevacizumab, the corresponding data sheet should be consulted.

¶In China only.

**The use of this product has EMA authorisation but is pending for obtaining funding conditions from HNS.

††Does not currently have EMA authorisation. This figure contains research data from products without EMA authorisation, with the only purpose of medical education. SEARCH study: sorafenib + erlotinib vs sorafenib + placebo. Trials in bold supported an approval.

Since 2017, new systemic therapies for advanced HCC have become available, resulting in a major paradigm shift in the treatment pathway.29 Patient survival following systemic treatment is expected at >2 years.2

Terminal stages

Patients with terminal stage HCC have major cancer-related symptoms, usually with impaired liver function. Due to the HCC burden associated with terminal stage disease, liver transplantation is not feasible, and additional non-HCC-related factors combine to provide poor short-term survival.2

Treatment of terminal stage HCC does not change expected survival and is of limited benefit. In such instances, management of symptoms and best supportive care (including palliative care) are mandatory.2 Patients with terminal stage HCC may be expected to survive approximately 3 months with best supportive care.2

OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival

References

1. Llovet JM, et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):6.

2. Reig M, et al. Journal of Hepatology 2022;76:681–93.

3. Yang JD, et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16(10):589–604.

4. Zhu X-D, et al. Genes & Diseases 2020;7:359–69.

5. Kardashian A, et al. Hepatology. 2023;77:1382–1403.

6. Ginès P, et al. Hepatology. 2022;75(1):219–22.

7. Vogel A, et al. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(6):801–5.

8. Roayaie S, et al. Hepatology 2013;57(4):1426–35.

9. Hack SP, et al. Future Oncol 2020;16(15):975–89.

10. Imamura H, et al. J Hepatol 2003;38:200–7.

11. Jung S-M, et al. J Gastrointest. Surg 2019;23(2):304–11.

12. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Hepatocellular Carcinoma V1.2023.

13. Norman EML, et al. Eur J Cancer Care. 2022;31:e13672.

14. Singal AG, et al. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001624.

15. Llovet JM, et al. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378–90.

16. Cheng AL, et al. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:4067–75.

17. Zhu AX, et al. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:559–66.

18. Cainap C, et al. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:172–9.

19. Kudo M, et al. Lancet 2018;391:1163–73.

20. Yau C, et al. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:149–60.

21. Finn RS, et al. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1894–905.

22. Ren Z, et al. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:977–90.

23. Qin S, et al. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:3002–11.

24. Kelley RK, et al. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:995–1008.

25. Abou-Alfa GK, et al. N Engl J Med Evidence 2022;1:EVIDoa2100070.

26. Finn RS, et al. Ann Oncol 2022;33(Suppl 7):S808–69.

27. Kudo M, et al. Ann Oncol 2022;33(Suppl 7):S808–69.

28. Qin S, et al. Ann Oncol 2022;33(Suppl 7):S808–69.

29. Su T-H, et al. Liver International. 2022;42:2067–79.

30. Yopp AC, et al. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21(4):128–95.