Welcome to MDS 2022

The 2022 International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, now in its 16th year, took place in Madrid, Spain, on 15–18 September 2022. At this year’s Welcome Ceremony, Pablo Martinez-Martin, Chair of the Local Congress Organizing Committee, was excited to relaunch the first in-person meeting since 2019. This years’ theme was ‘Scientific progress driving health and hope’ and the meeting featured an impressive program of sessions covering the latest advancements and research in the diagnosis and management of movement disorders.

“Our ever-expanding knowledge of movement disorders really translates into a significant improvement in quality of care and as a result of that improvement in patient quality-of-life.”

- Francisco Cardoso, President of the Movement Disorder Society (MDS)

MDS 2022 at a glance

Genetics

Roy Alcalay, New York, USA, discussed the integration of genetic testing into the management of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Genetic testing continues to be rarely offered to patients with PD in the USA. Dr Alcalay highlighted that in a survey of PD clinicians, 41% had not referred any patients with PD for genetic testing in the previous year, with >80% referring fewer than 11 patients. The most common reasons for not referring patients with PD for genetic testing are:

Four common reasons for not referring patients with PD for genetic testing

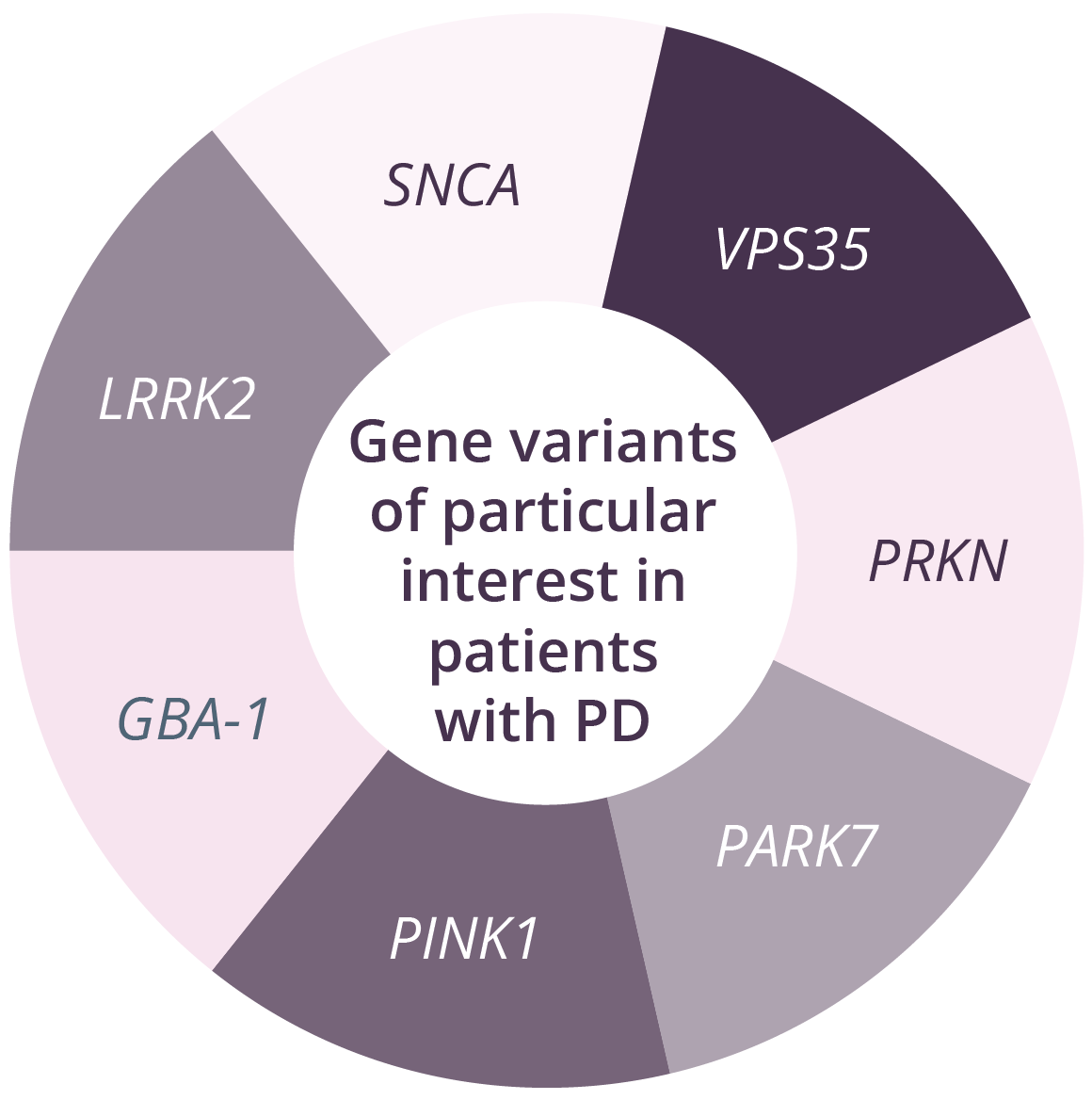

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in PD have increased the scope of biological knowledge about the disease over the past decade, with the identification of 90 independent genome-wide significant risk variants. Given that not all genome-wide significant risk variants are clinically meaningful, which variants should be included when testing for PD?

Genetic panels currently in use for patients with PD range from 5 to 62 genes. Of all genes linked to increased PD risk, those encoding glucocerebrosidase (GBA) and leucine-rich repeat kinase-2 (LRRK2) pathogenic variants are currently the most actively targeted for clinical development. There are a number of challenges for counselling following genetic testing in PD. For example, the list of genes/variants included in tests varies among different laboratories. However, genetic data may inform prognosis and also determine eligibility for clinical trials. In GBA carriers, counselling should include discussion regarding increased risk of Gaucher’s disease. Differential progression in genetic variant carriers has been reported in patients with PD. For example, individuals with PKRN or PINK1 typically have a young age of onset and slow motor progression, with cognitive impairment and non-motor symptoms being less common. In contrast, SNCA and GBA variants can lead to PD that appears idiopathic, with faster motor and cognitive progression compared with non-carriers, and GBA carriers have reduced survival compared with non-carriers.

“There is an urgent need to increase knowledge and reduce practical barriers to genetic counselling and testing in PD.”

- Roy Alcalay, New York, USA

Pathological mechanisms of PD

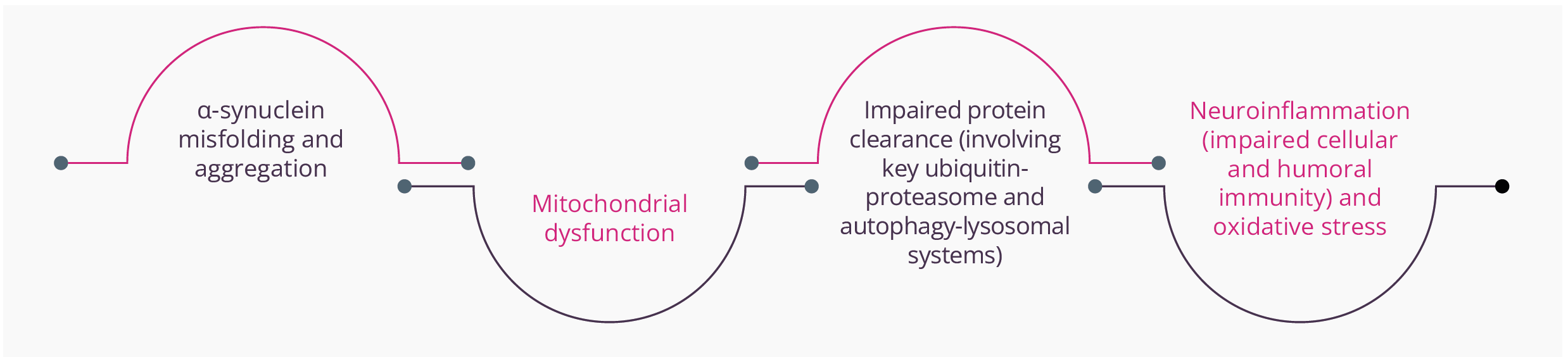

Nobutaka Hattori, Tokyo, Japan, discussed the pathological mechanisms of PD from pathogenesis through to biomarkers. The concept of ‘idiopathic’ PD as a single entity has been challenged with the identification of several clinical subtypes, pathogenic genes, and putative causative environmental agents. However, regardless of the underpinning aetiologies, several key molecular events and hallmarks have been consistently reported:

Key molecular elements and hallmarks reported within PD

Essentially, all of these mechanisms have the potential to promote apoptosis or necrosis. α-synuclein is natively unfolded and adopts a tertiary structure on certain biochemical interactions. Abnormal aggregation of the protein has been found to be toxic to dopaminergic neurons leading to neurodegeneration associated with PD.

Oxidative stress, PD gene mutations, and overexpression can influence α-synuclein conformational changes and its aggregation. Different forms/species of α-synuclein can also activate the neuroinflammatory response and ‘seed’ and spread α-synuclein pathology from cell to cell, providing the basis for therapeutic approaches from inhibiting its expression to reducing oligomeric species production and cellular transmission.

Mitochondrial dysfunction, such as reduction of mitochondrial complex 1 activity, has been identified in patients with PD and the use of inhibitors (e.g. rotenone) has been found to cause PD-like disorders in animal models. Mitochondria have also been shown to release a series of molecules (e.g. cytochrome C, ceramide and Apaf1) that can potentially trigger programmed cell death, while damaged mitochondria fail to provide the cell with ‘life-preserving’ energy. Of note, CHCHD2 mutations can cause mitochondrial-mediated cell death.

“The heterogeneity of pathological mechanisms in PD suggest that it is not a single disease entity.”

- Nobutaka Hattori, Tokyo, Japan

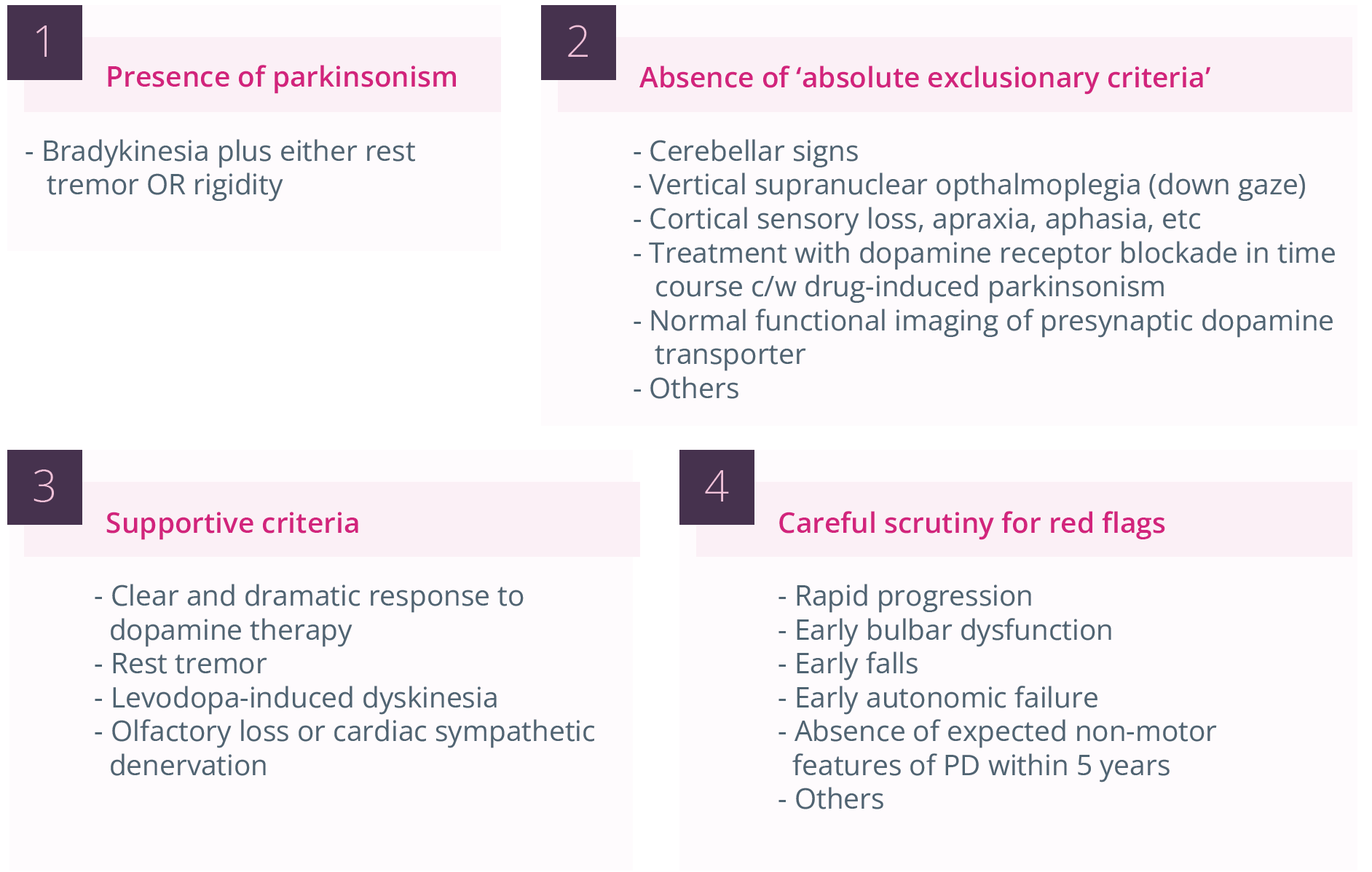

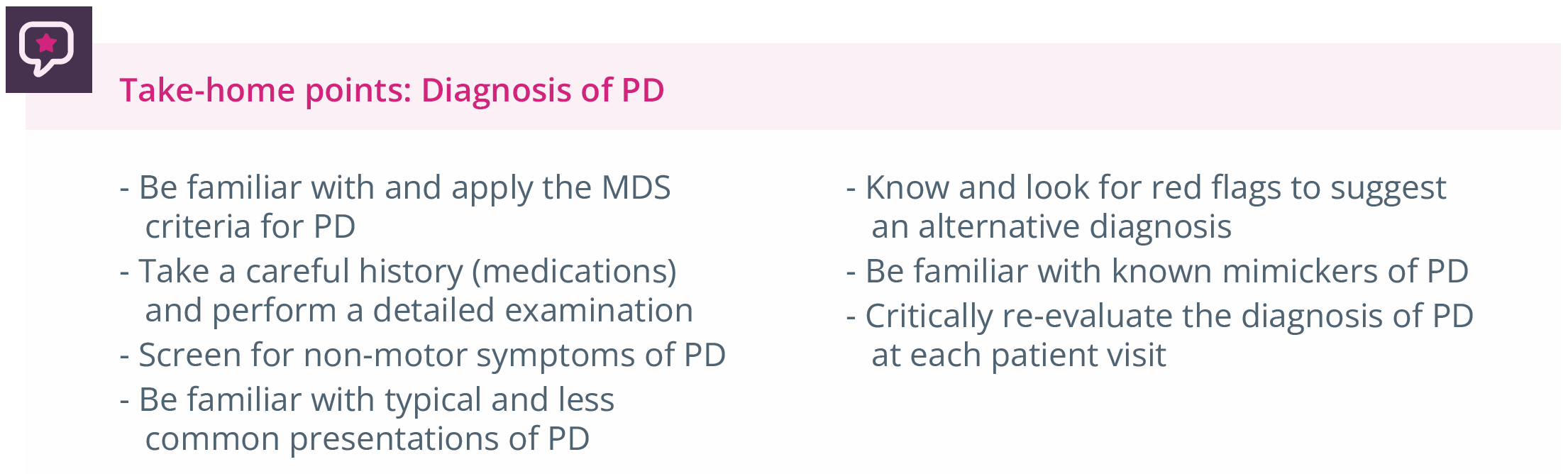

Diagnosis

Stephen Reich, Baltimore, USA, discussed pitfalls and perils in the diagnosis of PD in the clinic. The highest misdiagnosis rates appear to be for initial diagnosis, late-onset parkinsonism, and parkinsonism with dementia. When considering the diagnostic criteria for PD, there are a number of caveats that need to be considered. These include the need to provide an adequate trial of levodopa, and the understanding that parkinsonism may respond to levodopa but not dramatically, large amplitude PD tremor may not respond to levodopa, and in early PD there may be limited opportunity to improve symptoms with levodopa.

Challenges in the diagnosis of PD

In addition, specific symptoms/signs of early PD typically include its initial unilateral/asymmetric onset, classic resting tremor, and mild/subtle bradykinesia/cogwheel rigidity on the affected side. However, it is important to note that there appears to a spectrum of tremor in PD, with approximately 30% of patients with PD not exhibiting this symptom which can lead to incorrect diagnoses of stroke or musculoskeletal problems.

As only around 5% of individuals with PD present before the age of 45 years, PD is often not considered in the differential diagnosis of younger people. In addition, there are a number of false positives presenting in individuals across all age groups, which can lead to a misdiagnosis of PD. These false positives can include drug-induced parkinsonism, essential tremor, normal pressure hydrocephalus, and vascular parkinsonism. While PD is typically unilateral, drug-induced parkinsonism is usually symmetrical and atremulous, highlighting the need for the physician to take a careful drug history in patients presenting with possible symptoms of PD. Similarly, essential tremor is bilateral in presentation and associated with long period of latency (approximately 3 years) before an individual seeks medical help. Patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus present with impaired gait and balance, with little or no involvement of the upper limbs, and show no clinical benefits when receiving levodopa. In addition, physicians should be aware of the diagnostic criteria for Parkinsonian syndromes such as progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, multiple symptom atrophy, and dementia with Lewy bodies, as part of a differential diagnosis.

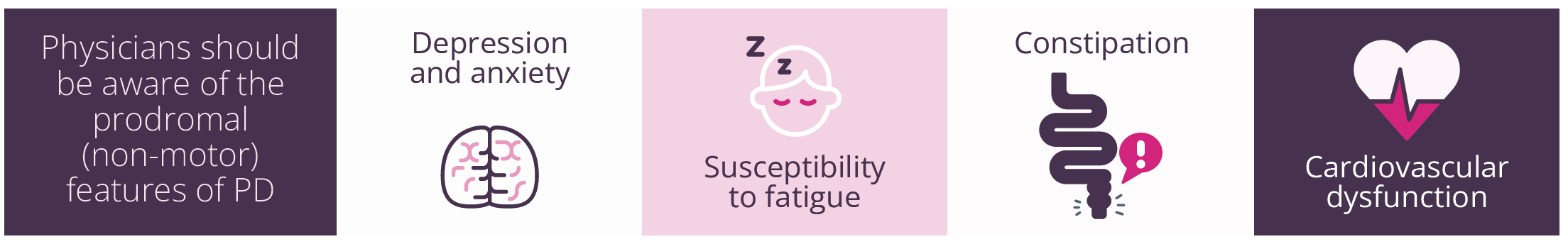

Prodromal (non-motor) features of PD

Summary of take-home points for PD diagnosis

“The most common mimickers of PD are parkinsonian syndromes.”

- Stephen Reich, Baltimore, USA

Daniela Berg, Kiel, Germany, briefly examined how to distinguish early-stage atypical parkinsonism from PD. In the early clinical diagnosis of atypical parkinsonism, it is important to consider any questions that the patient may have, honestly highlight any uncertainty in the diagnosis, and utilise current diagnostic criteria (along with supporting Apps) to distinguish between any relevant patient symptoms.

In addition, the physician needs to carefully ask the patient to describe specific motor and non-motor symptoms, and the use of available biomarkers to confirm the diagnosis should be considered. As a common parkinsonism, multiple system atrophy (MSA) can appear very similar to PD early on in the diagnosis and can even be somewhat levodopa responsive. ‘Red flags’ for MSA which make a clinician think that the diagnosis is not PD include rapid progression, prominent postural abnormalities such as tilting of the torso or flexion of the neck (this can also happen in PD, but can be more pronounced in MSA), and early dysfunction of voice and swallowing ability.

“Like PD, MSA is associated with abnormal accumulation of α-synuclein, although this accumulation takes place in a different cell type in the brain than it does in PD.”

- Daniela Berg, Kiel, Germany

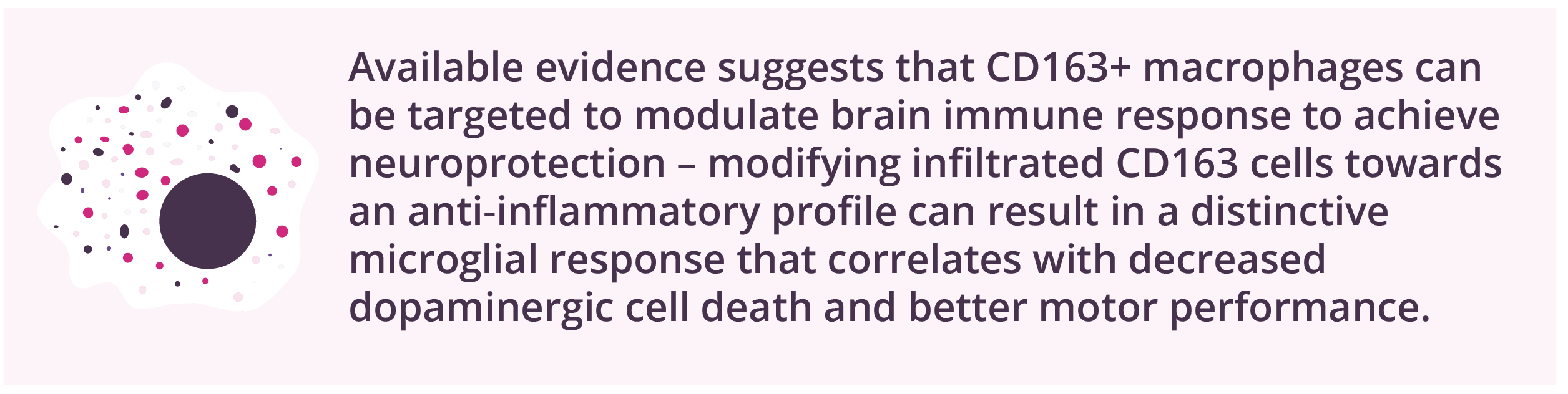

Targeting inflammation in PD

The immune response now evident in the progression of PD comprises both local microglia and other immune cells. Marina Romero-Ramos, Aarhus, Denmark, discussed immune response and inflammation as a target in PD. The immune response in PD occurs at a very early stage (prior to diagnosis) and involves both the brain and peripheral immune cells. The response is coordinated (between the brain and periphery) and associated with neurodegeneration. Changes in monocytes appear to be ‘dynamic’ based on disease stages and symptoms.

CD163+ macrophages can be targeted to modulate brain immune response to achieve neuroprotection

The brain environment is permissive for the infiltration of monocytes/macrophages, where they become activated in an event related to neuronal biomarkers.

The myeloid response in patients with PD is sex-specific, with different profiles being reported in men and women. For example, studies have reported inflammatory activation of monocytes in females with PD, with enrichment of gene sets associated with interferon gamma stimulation, while these activation patterns were more heterogeneous in males. The sex dimorphism is also true for innate immunity in the brain and for peripheral innate and adaptive cells. Major histocompatibility complex II expression on innate cells induces T-cell activation, wherein T-cells infiltrate the brain and influence inflammation; where modulation is possible (for example, using vaccination with α-synuclein), this can alter neuronal fate and promote protective immune responses in the brain.

“Both innate and adaptive immune cells are involved in the immune component of PD.”

- Marina Romero-Ramos, Aarhus, Denmark

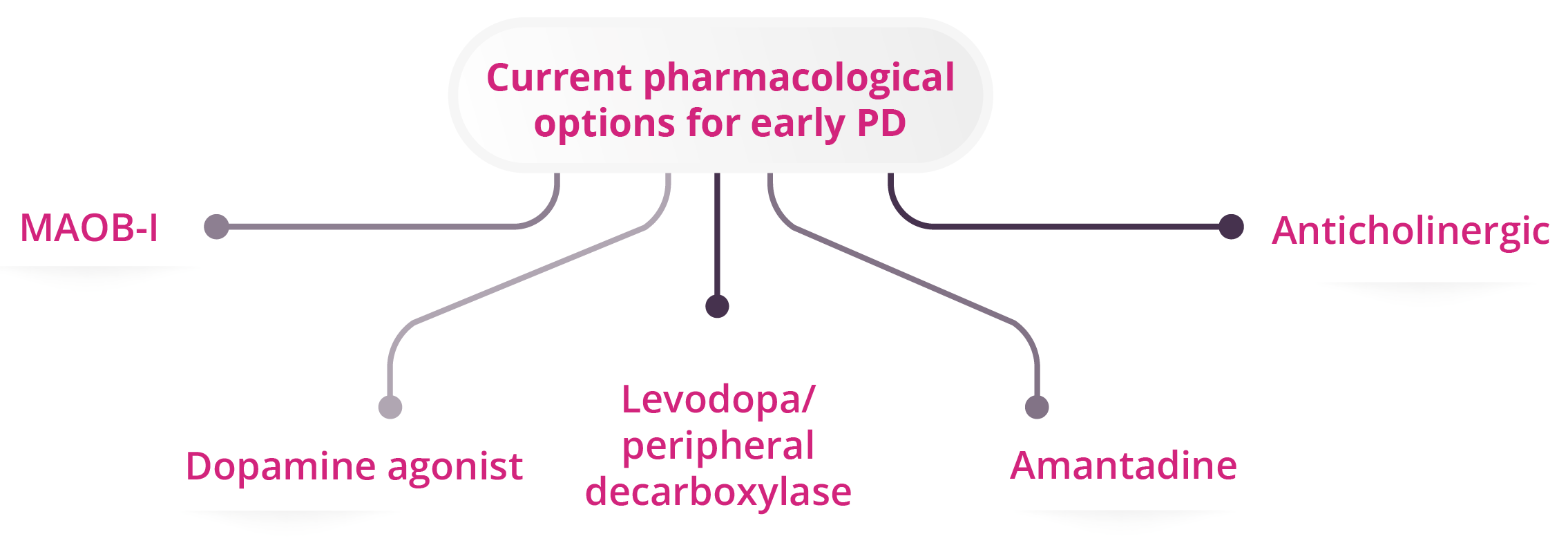

Treatment

Susan Fox, Toronto, Canada, discussed current therapeutic strategies in the early clinical stages of PD. Each patient needs to be treated/managed on an individual basis given that one treatment “does not fit all”. Dr Fox suggested using evidence-based medicine recommendations, but adapting these to fit patient’s needs and requirements. Non-pharmacological approaches to early PD include dietary supplements and exercise. While there is currently limited evidence to suggest any benefits with the use of supplements in patients with early-stage PD, there appears to be little harm (apart from cost implications) in taking these on a regular basis to support a healthy diet.

Of note, exercise needs to be sustained in order to provide any meaningful clinical benefit in early PD. A number of pharmacological options are available for use in patients with early PD, although none currently offer neuroprotection. Suitable patients should be encouraged to participate in clinical trials of novel agents in the hope of achieving improved clinical outcomes.

“Any dopaminergic drug will reduce PD symptoms, but oral levodopa has the best overall profile.”

- Susan Fox, Toronto, Canada

Five current pharmacological options for early PD

Annemette Lokkegaard, Copenhagen, Denmark, discussed the identification and management of motor complications in patients with PD. Indicators of advanced motor disease include ‘wearing off’, end-of-dose deterioration, fluctuations, and dyskinesia. In advanced state PD with confirmed motor fluctuations, subthalamic nucleus deep-brain stimulation has the highest level of evidence and is considered by many physicians to an efficacious treatment for dyskinesia, although treatment use has a number of possible surgical complications (e.g. infections and haemorrhage) and side effects (e.g. stimulation-induced dysarthria and dyskinesia). Use of an apomorphine pump may be suitable for treating OFF periods (when treatment wears off and patients feel worse) and troublesome dyskinesia, while levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel provides similar effects in managing OFF periods, with possible use in patients with troublesome dyskinesia. Both treatments improve quality-of-life (PDG8 or PDQ39) compared with best medical therapy.

“A multidisciplinary approach is important for the successful management of motor symptoms in patients with advanced/complicated PD.”

- Annemette Lokkegaard, Copenhagen, Denmark

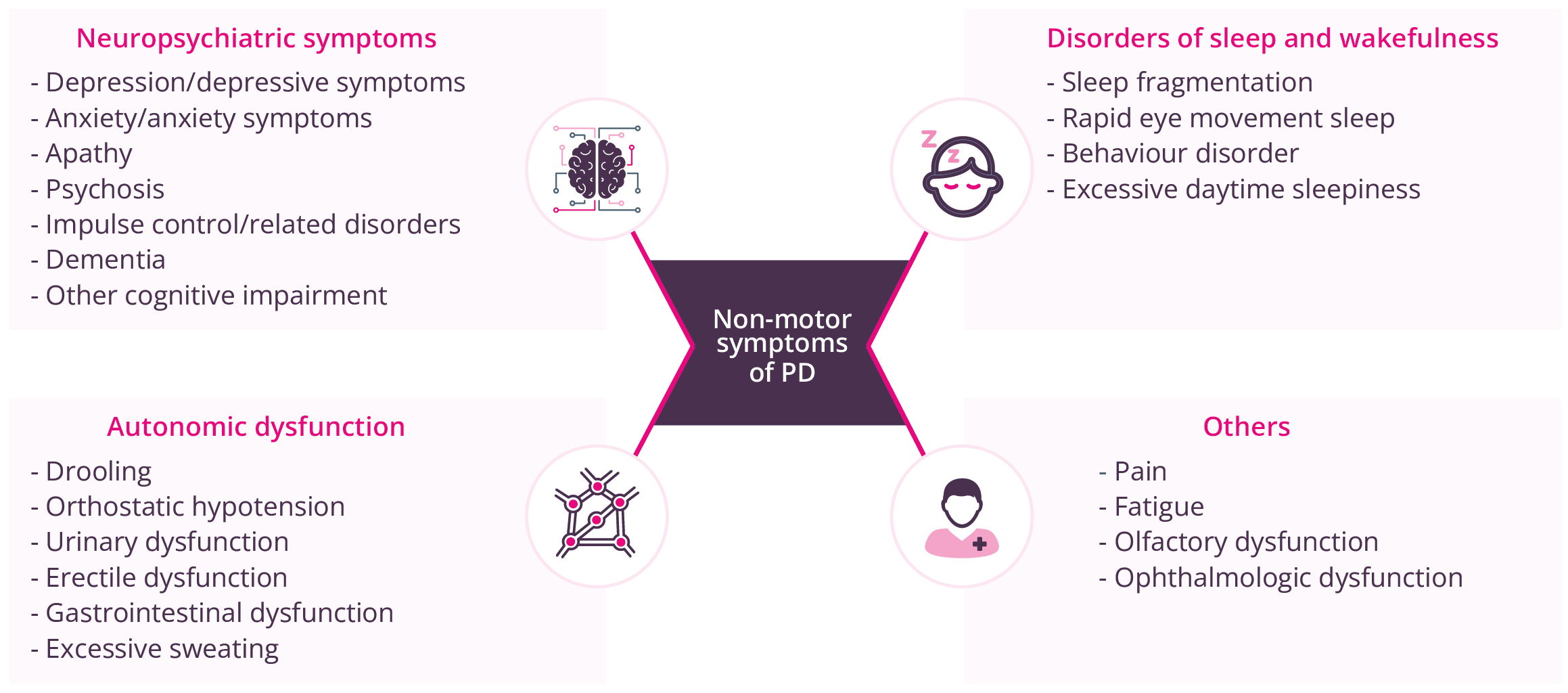

Priya Jagota, Bangkok, Thailand, discussed the identification and management of non-motor complications in patients with PD. There are a wide range of non-motor symptoms in patients with PD.

Non-motor symptoms of PD

Non-motor fluctuations in PD are similar to motor fluctuations with early morning wearing off, but can occur early on in the disease course before motor fluctuations, with prevalence and burden increasing with PD duration. Management of non-motor symptoms of PD pathology impact on a patient’s life. For example, depression and depressive symptoms, along with anxiety, are understandably common in patients at an early PD stage, given its chronic and progressive nature. However, agents such as pramipexole and venlafaxine have proven efficacy for these non-motor symptoms, and tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors/serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors may also have possible benefits. Effects of newer multimodal antidepressants on non-motor symptoms have yet to be studied. Physicians should aim to effectively manage any established comorbidities in patients with PD, while also considering other possible psychological aspects of PD such as a feeling of ‘loss of value’, increased dependency on others, and loss of freedom.

“We have to treat the patient as a whole, not just as a person with PD.”

- Priya Jagota, Bangkok, Thailand

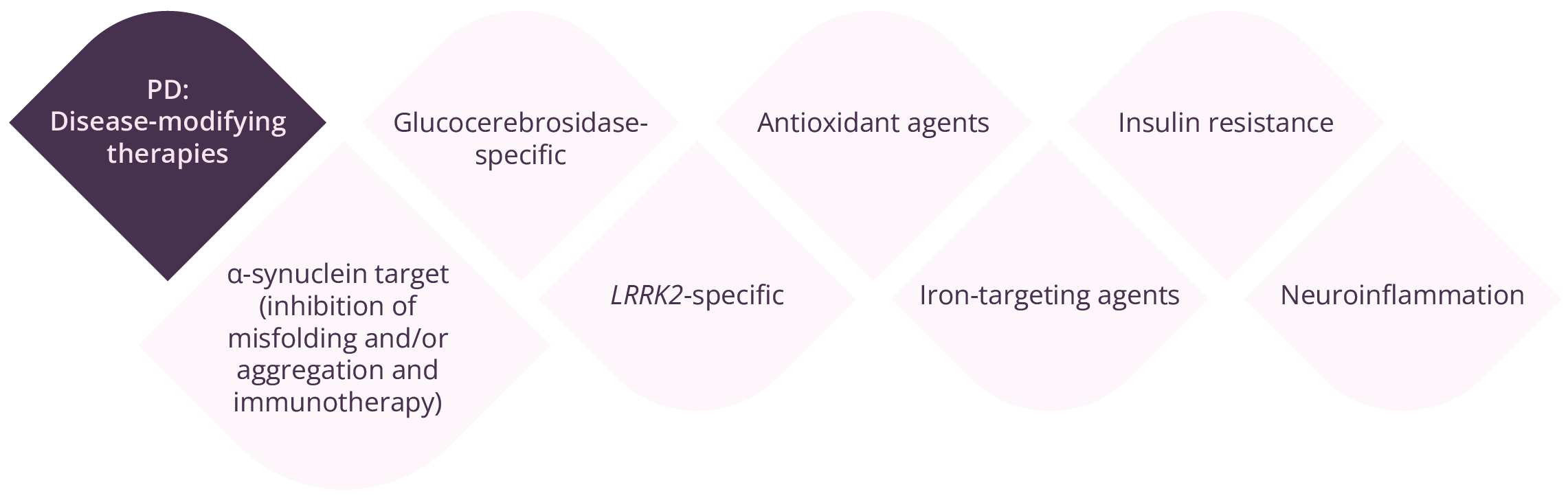

Margherita Fabbri, Toulouse, France, provided an update on ongoing clinical trials for PD. The development of disease-modifying treatments continues to be the main priority, with agents targeting α-synuclein and leucine-rich repeat kinase-2 (LRRK2) at the forefront of clinical studies. However, there is a significant need for target engagement measures for α-synuclein, and real clinical impact regarding disease modification has yet to be achieved. Regarding symptomatic treatment, there have been some interesting trials, such as the combination of dopamine agonists with low-dose monoamine oxidase inhibitors and the use of amantadine in early PD. For the management of motor complications in patients with more advanced disease, research is looking at drug repurposing strategies.

Disease-modifying therapies in PD

“Being able to measure the target engagement for α-synuclein is an ongoing need in clinical trials.”

- Margherita Fabbri, Toulouse, France

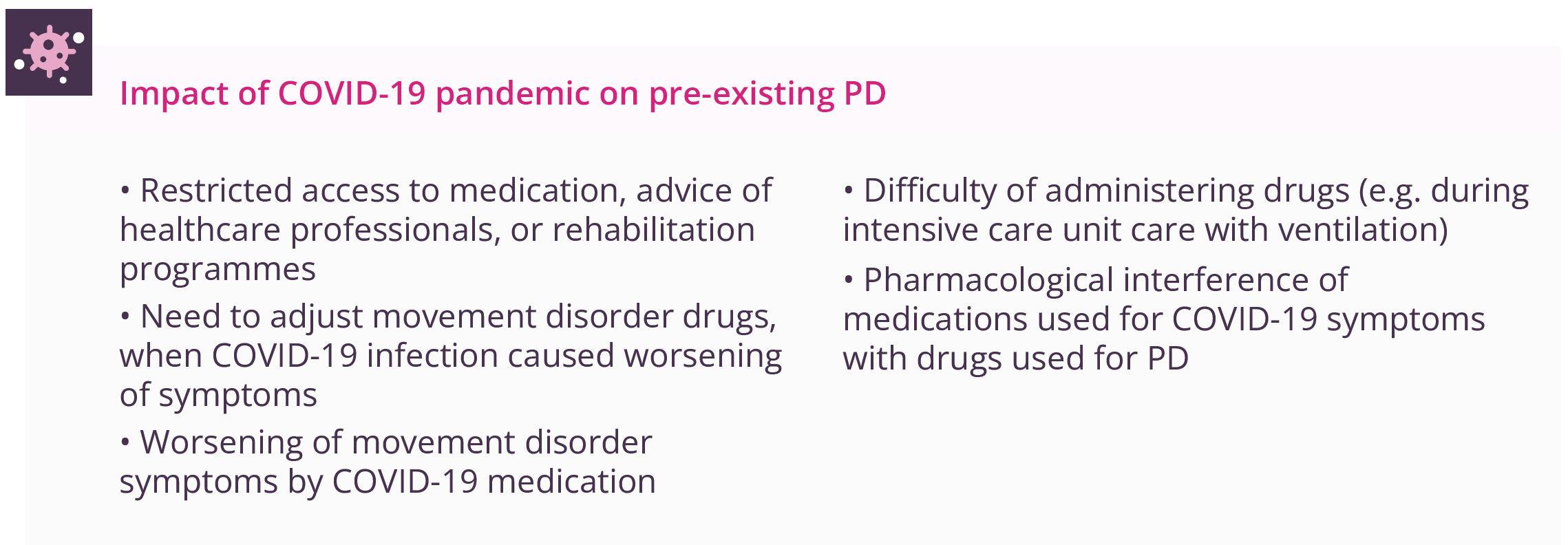

COVID-19 and PD

Susanne Schneider, Munich, Germany, discussed the potential influence of COVID-19 infection on PD aetiology. Early animal models suggest that SARS-CoV-2 may cause chronic low-grade inflammation that can lead to neurodegeneration. A retrospective cohort study (n=236,379) has provided evidence for substantial neurological and psychiatric morbidity in the 6 months after COVID-19 infection (34% with a neurological or psychiatric diagnosis, 13% first such diagnosis), with the whole COVID-19 cohort having an estimated incidence of 0.11% (0.08–0.14) for parkinsonism. The COVID-19 epidemic has also had substantial impact on those patients with pre-existing PD. Movement disorders remain a very rare side effect of COVID vaccines (frequency of 0.00002–0.0002), with tremor being most commonly reported.

“Parkinsonism is a potential long-term complication of COVID-19 infection.”

- Susanne Schneider, Munich, Germany

Present and potential future impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pre-existing PD

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation therapies are critical for optimising quality-of-life and daily functions for individuals living with PD. Thus, understanding the patterns of and under what conditions physicians make rehabilitation referrals is important for optimising care. Angela Roberts, London, Canada, discussed available evidence for uptake and adherence for rehabilitation in patients with PD. Rehabilitation services remain an important component of maintaining functional targets in movement disorders. However, a gap remains between ‘best practice’ and patterns of referrals for rehabilitation despite evidence supporting multidiscipline and proactive rehabilitation in PD. Data presented showed that only one third of patients are typically referred, with the majority of referrals being made to a single service (possibly reactions to falls or advancing disease), suggesting there may be missed opportunities for optimising care through proactive rehabilitation interventions. Expanding access through digital health should utilise remote assessment and technology platforms, telehealth, digital tools for symptom tracking that can be integrated into clinical decision-making pathways, and virtual platforms and network hubs that connect professionals, patients, and care partners.

“Referrals to rehabilitation services are underutilised for patients with PD, even in expert care centres, and multidisciplinary referrals are rare.”

- Angela Roberts, London, Canada

Actions needed for rehabilitation services within PD

Options for early rehabilitation for patients with PD

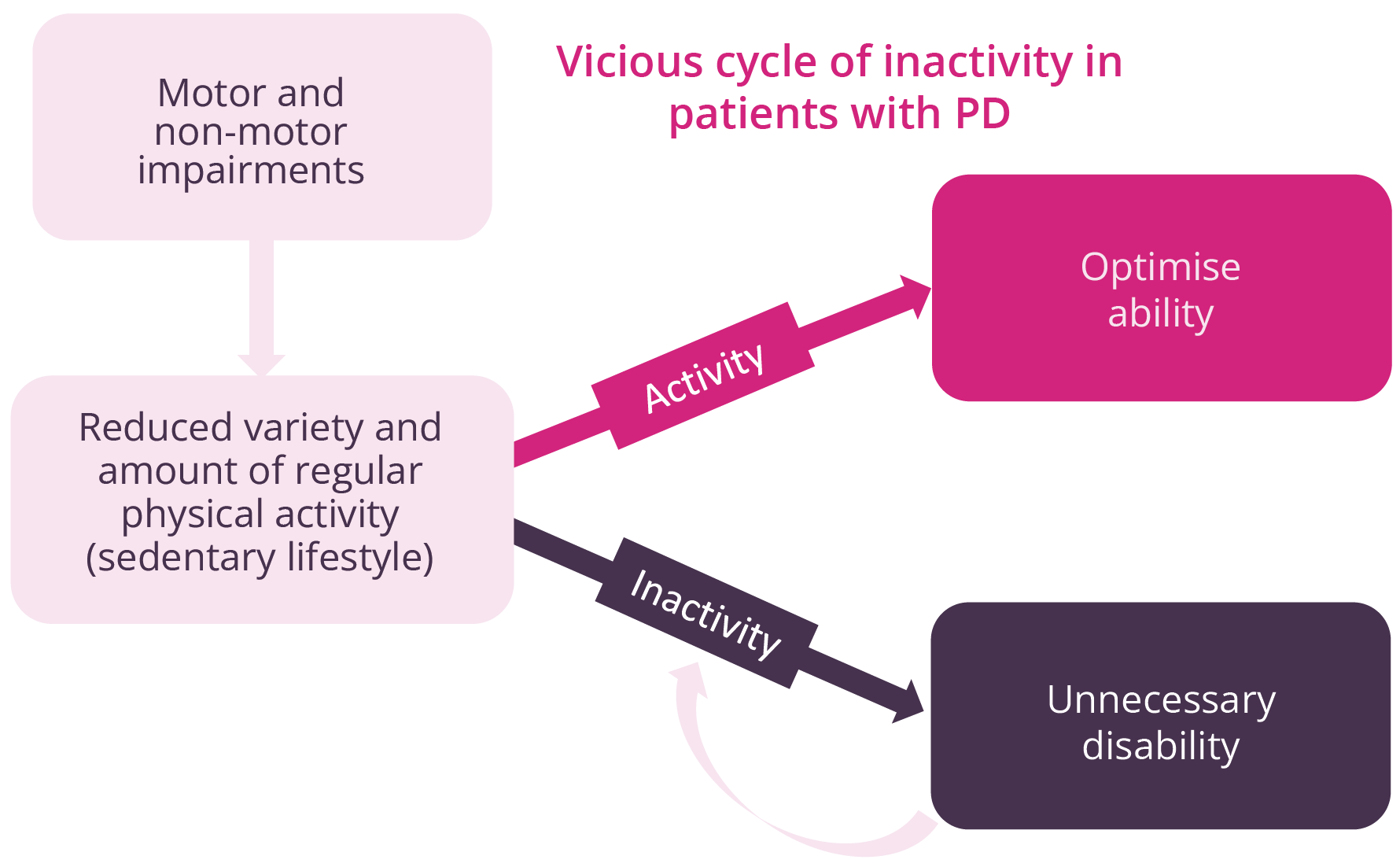

Natalie Allen, Sydney, Australia, discussed evidence for early rehabilitation in patients with PD. Disability occurs at an early stage of the disease, with motor and non-motor impairments. Regular exercise in animal models of PD has demonstrated reduced inflammation, α-synuclein expression, and mitochondrial function, while increasing neurotrophic growth factors such as dopaminergic neuron survival and dopaminergic neurotransmission. While such research is difficult to undertake in humans, available in-human studies have shown increased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor following exercise. Early rehabilitation incorporating exercise can delay disability, optimise abilities, prevent falls, and possibly attenuate PD. Thus, physicians need to be proactive and act at an early stage before disability and impairments start to cause problems. Early referral is advised to ensure that a suitable programme of rehabilitation can be developed for the patient. Of note, regular physical activity is associated with improved patient outcomes, such as quality-of-life, mobility, and physical function, while also reducing cognitive decline and disease progression.

The importance of improving activity for patients with PD

Regular physical exercise also appears to reduce the risk of patient falls (by around 25%) when initiated at an early disease stage, but appears less likely to offer such protection when started later on in the disease process, where it may even increase the risk of falls. Magnetic resonance imaging provides evidence of structural and functional neuroplasticity in motor and cognitive networks following regular aerobic exercise, with motor cognitive tasks providing supporting neuroplasticity. Harnessing such positive changes at the earliest possible opportunity (i.e. PD diagnosis) could improve long-term patient outcomes.

“Patients with PD are around 30% less active than the general population of similar age.”

- Natalie Allen, Sydney, Australia

Terry Ellis, Boston, USA, discussed key themes supporting the need for early and regular rehabilitation plus self-management approaches in PD. Although advances in medical management of PD have resulted in living longer, disability worsens over the course of the disease, and there are signs of disability even at the early stages of disease. Several studies reveal an early decline in gait and balance and a high prevalence of non-motor signs in the prodromal period that contribute to early disability. There is a growing body of evidence revealing the benefits of physical therapy and exercise to mitigate motor and non-motor signs while improving physical function and reducing disability. The presence of early disability coupled with the benefits of exercise suggests that physical therapy should be initiated earlier in the disease, thus highlighting the importance of self-management approaches to support such activities. Additional studies are needed to determine the underlying mechanisms of such behaviours (intention versus exercise ‘habit’ formation) to identify and promote optimal lifestyle behaviour change(s) at the earliest stage in PD.

Key aspects of self-management in PD

- Medication management

- Physical exercise

- Self-monitoring techniques

- Psychological strategies

- Maintaining independence

- Encouraging social engagement

- Providing knowledge and information

“Facilitating lifestyle changes, such as exercise and diet, requires more emphasis on behavioural interventions.”

- Terry Ellis, Boston, USA

Closing remarks