Welcome to ATS 2022

The 2022 Annual Congress of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) was held between May 13th and 18th in-person in San Francisco, USA, for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic shifted the congress to a virtual platform. In the Opening Ceremony, the ATS President, Lynn Schnapp, Wisconsin, USA, reflected on the previous two years and asked delegates to take a moment to recognise what the global respiratory community has been through since the pandemic began and how inspired she has been by the selflessness that every individual has demonstrated. She then brought in the sensitive issue of loss and how the community has experienced this in many forms, whether it was loss of patients, friends or colleagues, with missed milestones and a direct, significant impact on the global respiratory community. In light of this, Lynn Schnapp asked attendees to take a moment to recognise the sacrifices made and shared together. The contributions of the previous ATS Presidents, Juan C. Caledón and James M. Beck, were also recognised.

“ATS successfully pivoted to new paradigms and transitioned our meetings from in-person to virtual. Their steadfast, calm leadership and wise council has been instrumental to meet our community’s challenges”

- Lynnn Schapp, ATS President

Lynn Schnapp then highlighted ATS’ most notable accomplishments in the past year. Of these, the new logo and branding was praised for how it captures the mission and spirit of ATS by combining the representation of the lung with an aspirational arrow pointing upwards, signifying continuous, forward movement. Notably, the new ATS mission statement was outlined that captures the essence of what ATS aspires to achieve by accelerating global innovation for the advancement of respiratory health through multidisciplinary collaboration, education and advocacy. With this new mission as the driving force, all ATS activities will now fall under four pillars. In this in-depth report, recent advances in the diagnosis, treatment and management of interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), will be summarised and evaluated.

Year in Review: ILDs

Rupal J. Shah, San Francisco, USA, provided a review of key studies within the field of ILD published over the past year. Dr Shah organised her review of the year based on three major considerations of ILD: diagnosis, treatment and exacerbation.

The first study that she evaluated was an assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of endobronchial optical coherence tomography (EB-OCT) for usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). She noted that UIP was the most common pathologic correlate for IPF. The study was considered important to include in her summary as she recognised that accurate diagnosis of ILD is considered challenging and the gold standard remains multi-disciplinary review with surgical lung biopsy for patients where computerised tomography (CT) is not diagnostic. Many patients have comorbidities that preclude biopsy and are labelled unclassifiable, which makes the optimisation of future management challenging.

EB-OCT uses an optical imaging probe through the working channel of a bronchoscopy, providing in vivo 3D imaging of tissue with high resolution. The main advantages of this technique include its ability to image multiple sites in a rapid timeframe (10–15 minutes under conscious sedation and thus doesn’t require general anaesthesia). To assess whether EB-OCT was effective, specialities who would find it most useful in their practice were trained on how to carry out the procedure. Surgeons and general pulmonologists were given 10-minute standardised training on the EB-OCT technique. The ultimate goal was to accurately assess subpleural lung, so an on-site pathologist with expertise in these images was present. Three pathologists with expertise in ILD were also trained to read and interpret the images. In conclusion, it was considered feasible to teach bronchoscopic techniques to surgeons, pulmonologists and pathologists, allowing for interpretation with high reproducibility in a single centre. Overall, EB-OCT had high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of UIP patterns, particularly in mild-to-moderate forms of ILD. However, limitations of the study included heterogeneity in the non-UIP pattern due to a low number of cases. Despite this, the clinical implications of EB-OCT include its potential to change the diagnostic algorithm for ILD and assess changes in disease state over time.

The second study discussed by Dr Shah assessed the use of antifibrotic medicines, pirfenidone and nintedanib, in patients with IPF. The aim of this real-world evidence study was to determine how many patients with IPF were being prescribed antifibrotic medications. Current ATS/European Respiratory Society (ERS)/Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS)/Latin American Thoracic Association (ALAT) Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend treatment with nintedanib or pirfenidone after diagnosis of IPF, however, the safety profile of these drugs and their cost-effectiveness (particularly in the US) lead to concern about real-world adoption. This retrospective cohort analysis of a large US database identified 10,996 patients with IPF, including patients with both private and Medicare Advantage health plans.

Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend treatment with nintedanib or pirfenidone after diagnosis of IPF, however, the safety profile of these drugs and their cost-effectiveness (particularly in the US) lead to concern about real-world adoption. This retrospective cohort analysis of a large US database identified 10,996 patients with IPF, including patients with both private and Medicare Advantage health plans.

In conclusion, this retrospective cohort analysis found that uptake of antifibrotic therapy is low, there are gender disparities in prescribing and that there are high out-of-pocket monthly costs. Dr Shah also noted that we need to continue efforts to educate patients and providers on therapeutic options and the rationale for prescribing.

“We do need better ways to identify patients with IPF with higher accuracy; this is a plug for natural language processing or machine learning to really make sure we include the right patients”

- Rupal J. Shah, San Francisco, USA

The third study summarised by Dr Shah assessed whether cyclophosphamide plus glucocorticoids improved outcomes in IPF exacerbation compared with glucocorticoids alone.

There was a non-significant increase in mortality in the cyclophosphamide arm and no difference in morbidity or lung function at 6 months in survivors. It could be hypothesised that the difference in mortality may be related to infections given the immunosuppressive nature of cyclophosphamide, however, there was no difference in serious infections or adverse events in this trial. In conclusion, cyclophosphamide plus glucocorticoids did not improve mortality in IPF exacerbation when compared with glucocorticoids alone. In addition, baseline antifibrotic therapy was associated with a lower risk of death. An optimal approach to treating IPF exacerbations remains unclear and high quality evidence for glucocorticoid use in this patient population is required.

“We certainly need to advocate the reduction in cost of medications and make them accessible”

- Rupal J. Shah, San Francisco, USA

The final study included in this review summarised by Dr Shah was an open-label, pragmatic randomised clinical trial that assessed whether antimicrobial therapy in addition to usual care improved clinical outcomes in patients with IPF. The primary endpoint was novel compared with other trials in the same space as it looked at the time to first non-elective respiratory hospitalisation or all-cause mortality. She reminded delegates that changes in the lung microbiome have been associated with disease progression in IPF and that there are conflicting data on the role of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) and doxycycline in IPF. In conclusion, there was no impact of antimicrobial therapy when compared with usual care in IPF. Currently, there is no evidence to support the use of chronic antimicrobials in patients with IPF. This study had some limitations as there was a lack of placebo control, IPF was designated at the local site and there was no phenotyping of the microbiome prior to enrolment. However, a strength of this study was its attempt to utilise a pragmatic approach with few exclusion criteria to address its aims within a real-world population. Dr Shah encouraged delegates to read other papers within the bibliography of her Year in Review that she couldn’t include due to time constraints, particularly the international multicentre study entitled ‘Outcome of hospitalisation for COVID-19 in patients with ILD’ by Drake TM, et al. (2020).

Challenges in the early detection and diagnosis of ILD

Diagnostic evaluation for patients with ILD

In an interactive Meet the Experts session, Shweta Sood, Philadelphia, USA, provided an overview of how to optimally evaluate ILD at diagnosis.

Dr Sood highlighted that a thorough history and examination is the most important step to narrow a differential diagnosis, stressing that obtaining a quick patient history is not sufficient as this tends to be non-specific. The most common differentials are often IPF, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, sarcoidosis and connective tissue disease-associated ILD (CTD-ILD).

“History is valuable because patients often present with non-specific symptoms such as cough and dyspnoea. It’s important to do a thorough history to narrow your differential”

- Shweta Sood, Philadelphia, USA

A thorough history is key because there are seven major groups to consider. Exposure history is particularly relevant, so probing whether a patient has been exposed to mould, birds, certain medications and thoracic radiation could narrow differential diagnosis. Dr Sood suggested asking patients what their occupation is as well as their smoking history. In addition, it is key to identify patients with a familial history of ILD.

Dr Sood gave an overview of physical exam features when assessing whether a patient may have ILD. She noted that, although carrying out lung exams are standard, it’s important to also consider the condition of the skin on the face, hands and neck as this could help to isolate patients with ILD rather quickly. For example, Dr Sood would often ask patients whether their fingertips turned blue in cold weather to determine a potential sign of ILD.

Dr Sood then outlined the most common ILD comorbidities and strongly recommended screening for them where possible.

Dr Sood evaluated the use of pulmonary function tests (PFTs) and walk tests in day-to-day clinical practice. She noted that these tests collectively can help establish disease severity, monitor disease progression, assess response to therapies and could even portend prognosis. Dr Sood then outlined the importance of noting UIP and fibrotic patterns on CT as this could narrow differential and influence biopsy choices. At high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) stage, she stressed why detecting UIP matters because any observed honeycombing may be associated with worse survival. Dr Sood then provided a summary of pivotal trials and how the findings of these demonstrate why narrowing differential diagnosis matters.

In conclusion, a thorough work-up can identify a cause for ILD and narrow differential. By integrating patient history, exams, tests and HRCT results, differential diagnosis could be narrowed further and may predict prognosis.

Radiologic and serum biomarkers to assess subclinical ILD in community-dwelling adults

An educational session applied the apt analogy of ‘catching the bull before it destroys the shop’ to showcase how identifying the prevalence of interstitial lung abnormalities (ILAs) and rates of progression in patient populations at risk of developing progressive fibrosis could complement clinical considerations for ILA management, follow-up and potential therapeutic options.

Anna Podolanczuk, New York, USA, gave an overview of potential radiologic and serum biomarkers that could pre-empt subclinical ILD in community-dwelling adults. She noted that over the past two decades, we’ve learnt a lot about the pathogenesis of progressive pulmonary fibrosis. She stated that there’s hope to identify a biomarker to pinpoint early processes before patients develop symptoms and clinical disease. Quantitative CT imaging can detect early lung injury and remodelling, even in normal-appearing lung. The simplest of which is a lung density-based measure, which looks at the volume of the lung on CT scan and identifies any increased lung attenuation. A more sophisticated texture-based measure incorporates reticularity and quality of vacuoles on CT to determine how much of the lung is involved by inflammation and fibrosis. The most sophisticated of these methods utilises machine-learning algorithms to identify abnormal areas of the lung.

“An ideal biomarker of subclinical ILD should show us how to identify early biologic processes that lead to progressive pulmonary fibrosis”

- Anna Podolanczuk, New York, USA

Dr Podolanczuk outlined the key results of her recent study published in American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, which found that high attenuation areas (HAAs) were found to be associated with all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 1.55 [95% CI 1.37–1.77]; p<0.001), ILD hospitalisations (HR 2.6 [95% CI 1.9–3.5]) and death (HR 2.3 [95% CI 1.7–3.0]). In addition, deep learning algorithms such as HAA were found to enhance the accuracy of radiologic biomarkers for subclinical disease. Blood biomarkers such as matrix metalloproteinase-7 and monocytes that are prognostic in clinical disease may also identify subclinical disease. She then highlighted that large-scale proteomics could uncover novel protein biomarkers of ILA. In summary, quantitative CT-based biomarkers and a combination of blood biomarkers may be useful for the detection of subclinical ILD, but few are currently available for clinical use.

“There are several advantages to using CT-based biomarkers for early detection as they are objective, easily deployable and can be easily integrated into existing care”

- Anna Podolanczuk, New York, USA

Autoimmune-associated ILD

Virginia D. Steen, Washington, USA, and Mark J. Hamblin, Kansas City, USA, presented an overview of autoimmune-associated ILD and how to approach individual patient cases. Dr Hamblin began by describing the set-up to the multidisciplinary ILD conference within his institution and how the panel was predominantly radiologists, pathologists and ILD specialists until March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic began. However, from then on, a monthly ILD community outreach multidisciplinary conference was hosted over Zoom and Dr Hamblin opted to include rheumatologists across Kansas in these discussions and noted this was “one of the best decisions” he could have made as rheumatologists contributed immensely to the educational content. He urged the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to managing autoimmune-associated ILD, particularly involving rheumatologists as well as pulmonologists.

“I would encourage you to pick up the phone and talk to your rheumatology department and discuss some of these cases of autoimmune-associated ILD because they provide invaluable insights into more challenging diseases”

- Mark J. Hamblin, Kansas City, USA

Dr Steen highlighted that ILD is common among autoimmune diseases, particularly in antisynthetase syndromes and systemic sclerosis. She mentioned that there are several challenges to diagnosing autoimmune-associated ILD. An initial step required is a PFT as standard. Patients reporting dyspnoea should undergo complete PFTs. Carrying out a chest X-ray alone, particularly for ILD, is not adequate, as a HRCT would also be useful. Monitoring extrapulmonary manifestations could be important as puffy fingers could be a signifier. Perhaps ask the patient whether they have recently changed their ring size. In addition, cold sensitivity in their hands could also be important to pinpoint a potential diagnosis of autoimmune-associated ILD. Therefore, as well as listening for crackles in the lungs to diagnose autoimmune-associated ILD, the condition of the hands of the patient should also be a focus.

Basic blood tests are generally an initial step in evaluating a patient, however, many ILDs may not have specific abnormalities. Some ILDs associated with autoimmune diseases may exhibit an antibody signature, for example, autoimmune-associated autoantibodies (ANAs) could include antinuclear antibodies (detected by an immunofluorescence assay and enzyme immunoassay), rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide. Anti-topoisomerase (Scl-70) is the most common antibody associated with severe ILD.

The imaging features of a HRCT scan and how they are distributed could point to diagnostic patterns.

There are multiple factors that could provide evidence of progression in chronic fibrosing ILDs.

Dr Steen and Dr Hamblin presented two interesting patient cases of rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-ILD and systemic sclerosis (SSc)-ILD.

In Case 1 (RA-ILD), a HRCT chest scan revealed a UIP pattern with evidence of subpleural reticulation. What we know in RA is if the patient presents with a UIP pattern, no matter where it is located in the scan, there is a high risk of disease progression. Eighteen months later, Case 1 complained of increasing dyspnoea with cough and showed no improvement with oral antibiotics. Repeat PFTs showed a decrease in forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1), total lung capacity (TLC), and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLco). Repeat HRCT scan showed progres- sive RA-ILD with organising pneumonia and cavitary nodules. In summary, pulmonary complications of RA may involve the pleura, airways, lung parenchyma or pulmonary vasculature. ILD is the most common of these pulmonary complications, occurring in up to 10% of patients with RA. A challenge in monitoring patient cases like this one is that RA-ILD is multifaceted and not all risk factors are known. In addition, these patients can be challenging as they could have long-standing RA and may not notice a shortness of breath as their level of exercise may be low. When tackling a similar case, it is recommended to maintain a high index of suspicion by evaluating with PFTs and chest HRCTs.

In Case 2 (SSc-ILD), the mistake that led to the initial diagnosis of undifferentiated connective tissue disease (UCTD) with inflammatory arthritis was that the observed nucleolar pattern and puffy fingers should have been considered a potential sign of scleroderma. PFTs revealed severe disease, with FVC at 56% and FEV1 at 61%. A HRCT chest scan revealed ILD with a non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) pattern. ILD is considered the leading cause of scleroderma-related deaths in up to 35–40% of patients. Risk factors for SSc-ILD are considered to be: male gender, African-American race, older age and auto-antibody status (+Scl70, +U1 ribonucleoprotein [RNP] and +U3 RNP). It is recommended to screen patients with PFTs and HRCT scans for early detection of SSc-ILD. A multidisciplinary discussion is also encouraged to establish diagnosis of SSc-ILD and guide therapy options.

Recent analyses of IPF patient registries and the pivotal phase III INBUILD trial

Peter HS. Sporn, Chicago, USA, presented recent findings of an analysis of the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry (PFF-PR) data from its inception in March 2016 until May 28, 2021. Inpatient hospitalisation rates and emergency room visits were collected for various types of ILD, with analyses of all hospitalisations and respiratory-related hospitalisations performed. An unadjusted Cox proportional hazard analysis compared the risk of death or transplant between these patients that were hospitalised versus not hospitalised. Of the total 1989 patients included in the analysis, 61.6% and 16.7% of patients were diagnosed with IPF and CTD-ILD, respectively; the other 21.7% of patients had either chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, non-IPF idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP), or ‘other’ diagnoses.

Dr Sporn noted that hospitalisations were common in ILD. Respiratory-related hospitalisations portended a worse prognosis than non-res- piratory hospitalisations. The rate of hospitalisation amongst patients with IPF was 61.6% (n=1226). In addition, he highlighted that hospitalisations in patients with IPF were associated with a worse prognosis than those with ILD.

In another analysis of data from the PFF-PR, 2018 Fleischner and ATS/ ERS/JRS/ALAT diagnostic criteria for UIP were applied to a population of patients with clinically diagnosed ILD from the PFF-PR to determine whether visual and quantitative CT variables predicted treatment-free survival (TFS). Nine-hundred and seventy-six patients with baseline chest CT scans were included. In a multivariate Cox model, definite, probable and intermediate visual CT patterns in patients with PFF (n=634; c=0.67) were HR 1.78 (95% CI 1.12, 2.85), HR 1.25 (95% CI 0.73, 2.12), and 1.41 (95% CI 0.90, 2.22), respectively, with statistical significance shown in definite visual CT patters (p=0.016). Data-driven textural analysis was the strongest predictor of TFS (1.05 [1.04, 1.06]; p<0.001). In conclusion, visual and computer-based quantitative CT variables were considered significant predictors of TFS in a heterogeneous population of patients with fibrosing ILD.

As IPF is a progressive fibrosis ILD with an unpredictable course, identifying prognostic biomarkers remains an unmet need. The IPF-Prospective Outcomes (IPF-PRO) Registry (NCT01915511) – an observational US registry that enrolled patients with IPF that was diagnosed or confirmed in the past 5 months – was analysed to examine associations between select circulating proteins and respiratory death or lung transplant. In addition, the variable importance of these circulating proteins as predictors of these outcomes was recently assessed. The cohort comprised 299 patients followed for a median of 39.9 months. Fifty proteins were quantified in plasma taken at enrolment using multiplexed ELISA. Jamie L Todd, Durham, USA, presented the findings of this analysis, noting that 124 patients (41.5%) experienced respiratory death or lung transplant. Dr Todd concluded that, in patients with IPF, select circulating proteins such as intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9) were associated with a risk of mortality and conferred information independent of clinical measures. The implications of these data are that, with further optimisation, multiprotein-inclusive algorithms may provide meaningful risk stratification in patients with IPF.

An analysis of time-from-first acute exacerbation to hospitalisation or death in ILDs in the phase III INBUILD trial (NCT02999178) was recently conducted, with data pooled from patients who had received nintedanib or placebo. ILD diagnoses (N=663) included hypersensitivity pneumonitis, autoimmune disease-related ILDs, idiopathic NSIP, unclassifiable IIP and other fibrosing ILDs. Fifty-eight (8.7%) of patients had a risk of acute exacerbation.

The estimated risk of hospitalisation ≤180 days after an acute exacerbation was 90.6% (95% CI: 81.8, 99.4). Acute exacerbations of progressive fibrosing ILDs other than IPF may have a similar impact on outcomes as acute exacerbations of IPF. The risk of acute exacerbation was higher in the following patients:

Athol U. Wells, London, UK, presented the results of a sub-study of the INBUILD trial (NCT02999178) in which changes in radiological features in patients with progressive fibrosing ILDs were treated with nintedanib. Patients had been randomised to receive nintedanib or placebo, stratified by HRCT pattern (UIP-like fibrotic pattern or other fibrotic patterns). In this exploratory sub-study, the effects of nintedanib on markers of lung fibrosis on HRCT were assessed, with HRCT scans obtained at baseline and Week 52. Dr Wells noted that a small change in overall extent of fibrosis and HRCT was observed over 52 weeks. In patients with fibrotic patterns other than UIP, nintedanib was associated with a lower risk of worsening in the extent of ground-glass opacification.

Management of ILDs

Fulminant ILDs presenting with acute respiratory failure

In an interactive Meet the Experts session, Stacey-Ann Whittaker Brown, New York, USA, presented her insights on the optimal management of fulminant ILDs presenting with acute respiratory failure. Dr Whittaker Brown outlined that acute exacerbation of IPF could either be triggered acute exacerbation (e.g. due to infection, drug toxicity or aspiration) or idiopathic acute exacerbation (i.e. no trigger identified).

She then gave an overview of the most commonly described non-IPF ILDs: CTD-ILD (such as scleroderma and RA), unclassifiable (which constitutes a large proportion due to the challenges of lung biopsies in this patient population), NSIP and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Dr Whittaker Brown pointed out that there is some disagreement in the literature on whether patients with non-IPF experience acute exacerbations at the same rate as those with IPF. The risk factors for poor prognosis in non-IPF have been identified as:

- Non-NSIP

- Low lung function (TLC, FVC and DLco)

- Fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (fHP): bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) neutrophilia or low BAL lymphocytosis

- fHP: UIP at biopsy

Dr Whittaker Brown considered it useful for context to provide an overview of a study by Polke M, et al. (2021) that assessed the differences in prevention, diagnostic and treatment strategies for acute exacerbation of IPF (AE-IPF) in specialised and non-specialised ILD centres worldwide. Pulmonologists working in these centres were invited to complete a survey designed by an international expert panel. Of 313 ILD pulmonologists surveyed, >70% were in agreement on the following tests only:

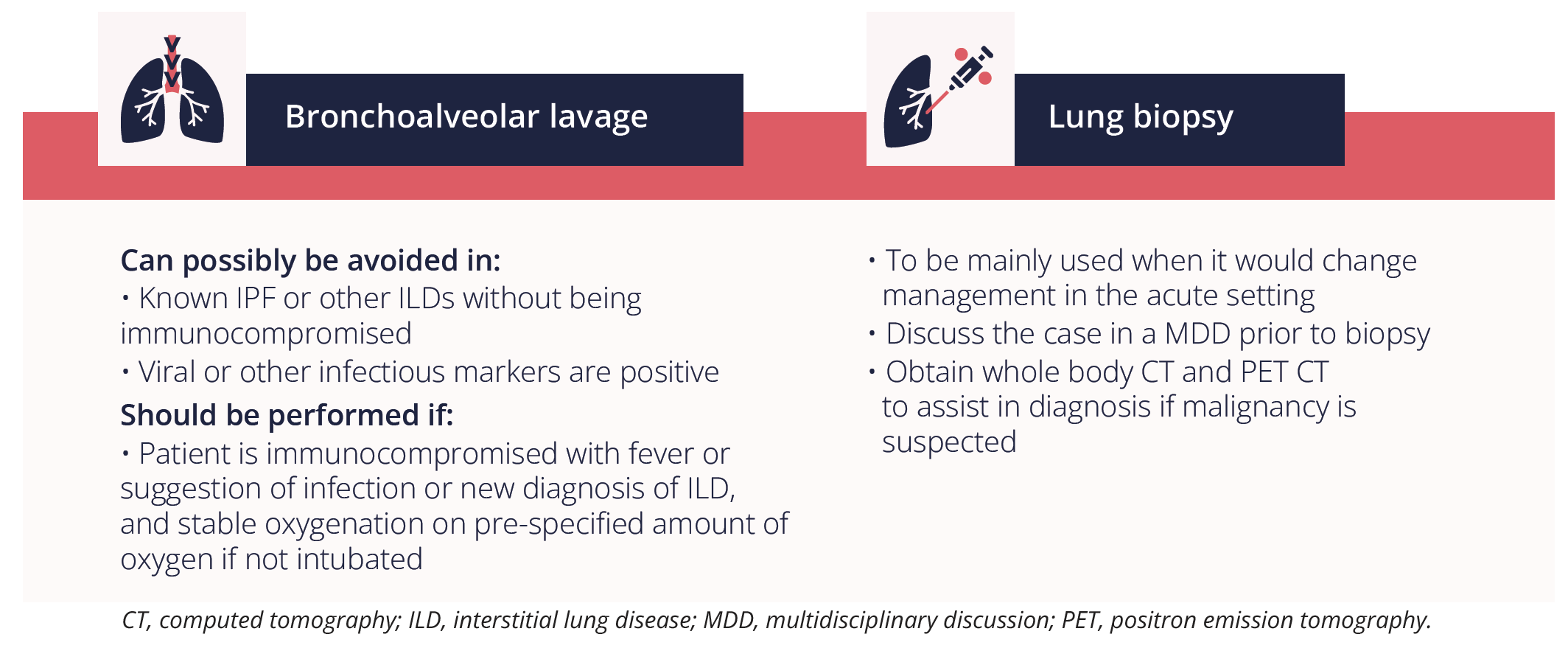

Therefore, approaches to the diagnosis of AE-IPF were comparable in specialised and non-specialised centres. Dr Whittaker Brown then provided her insights on the importance of each stage of diagnostic work-up:

Dr Whittaker Brown then highlighted the main considerations for the management of acute exacerbation of ILD.

Firstly, she emphasised the importance of ‘do no harm’ by:

- - Considering invasive procedures carefully and ensuring they are safely performed

- - Limiting experimental, high risk therapies outside the context of a clinical trial

Dr Whittaker Brown provided an overview of when to consider using invasive procedures for acute exacerbation of ILD.

Secondly, Dr Whittaker Brown highlighted the importance of considering the trigger of the acute exacerbation in patients with ILD and whether it was:

Thirdly, Dr Whittaker Brown suggested to check whether the patient is responding to “standard” therapy or if other supportive strategies need to be implemented:

In summary, consider the suitability and safe implementation of invasive diagnostic procedures and standardise your institution’s parameters of when these should be performed. The exacerbation type should be considered: if triggered, implement direct management towards the trigger; if idiopathic, implement direct management towards the underlying disease. Timing is everything with advanced supportive measures, so always consider transplantation status and ease of reversibility prior to intubation, as delaying transplantation may worsen clinical outcomes.

Closing remarks

Looking ahead to next year’s congress, ATS is planning another live, in-person event in Washington, DC, which will be complemented by a rich array of online content. Delegates should save the date for ATS 2023 on May 19th-24th.